A reader has brought to my attention a new biography of photographer Edward S. Curtis, who over the course of thirty years in the early twentieth century, documented native American populations. I am certainly going to read this book by Timothy Egan; so I reserve judgment on that. But reading the review in the New York Times, reintroduced me to the photographs of Curtis and that is always a welcome experience.

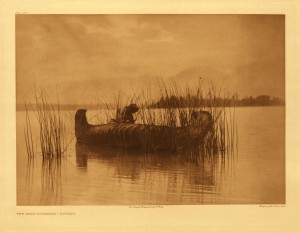

Figure 1 – One of Edward S. Curtis’ most popular images “Rush Gatherer, Kutenai, 1911” from the collection of the LOC.

The topic is a complex one. We are confronted with the imperial age view of manifest destiny, the glorification of the American west, and the worship and emulation of the manly, personified by Theodore Roosevelt. At the same time, Curtis was contemporaneous with Franz Boas, “the father of modern anthropology,” and the emergence of the concept of cultural relativism, itself a hugely complicated and controversial idea. The attempted eradication of native peoples and native cultures is a terrible blot on our moral credibility as a nation. Curtis, with his concept of “the vanishing race,” believed that he was documenting the demise of the native peoples. In reality he was documenting their transition into modern times.

Fortunately, our focus here is on the photographic, and Curtis was a grand master of the photographic image. His work is monumental. His goal was to document every Native American tribal group then in existence. He filled twenty volumes with sensitive and beautifully crafted photographs. As an ethnographic record it rivals, indeed eclipses, Roman Vishniac’s “A Vanished World,” which documents the end of Hebraic culture in Eastern Europe on the eve of World War II.

Curtis has been criticized for staging or posing many of his images, albeit to recreate well researched scenes. It is important to recognize the limits of contemporary emulsions. No less posed and staged were John Thomson’s equally significant photographs of nineteenth century London street life, published 1876-7 and taken under much less trying circumstances. The role of photographer as a chronicler of visions that will never be seen again is both important and profound.

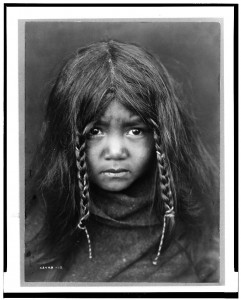

Figure 2 – Edward S. Curtis, “Quilcene Boy, 1913,” from the collection of the LOC.

I really had no understanding of just how prodigious Curtis’ output was, until I started researching this blog and visited the Library of Congress (LOC) and Northwestern University pages dedicated to providing a resource for Curtis’ work. There is also an excellent resource at the Edward S. Curtis Gallery, which offers many of these wonderful works for sale. There are hundreds of beautiful images of people in portrait or posed in the course of their daily and spiritual lives, as well as images of their handiwork. Always compelling are the beautiful images of children. It invariably haunts me to see the flash and beauty in the eyes of children in images now a hundred years old. The flash is there for eternity, while the individual is long gone. Photography, more than any other form of portrait art, has this effect, and it is a tribute to Curtis’ impact that native Americans today use his photographs to teach the current generation of their children about their cultural heritage.