We have talked a lot about the power of images and how, in the wrong hands, they can be abused. And isn’t everybody just about sick of the current election cycle and all of the misinformation and out of context imagery? The latest is the Romney ad purporting to show President Obama “bowing” to Chairman Hu of China (I’m not going to perpetrate that here, but do check out the video clips by the Fact Checker at the Washington Post).

The point is that this kind of manipulation, beside, as it is meant to, diverting us from the real issues, is pandemic in our sound-bite, screen-flash world. Which is not to say that it hasn’t been around for a long time or that it wasn’t just as insidious in quieter and “more reflective?” times.

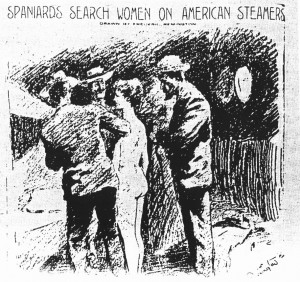

So I was musing the other day about the great iconic image of yellow journalism (see Figure 1) of a woman being strip searched by leering Spanish officials on the American ship Olivette in Havana harbor in 1897. There is some controversy now about the role played by yellow journalism in the instigation of the Spanish American War. That aside, this picture by Frederick Reemington was published as an illustration to an article by journalist Richard Harding Davis “Does our Flag Shield Women?,” in William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal on Feb. 12, 1897. Reemington had left Cuba weeks before the incident occured.

Not surprisingly the circulation of the New York Journal soared, and, as a result of the article, public furor frothed to hydrophobic proportions. The United States Congress demanded an explanation from the Spanish. The truth, needless-to-say, was left

behind. The truth was that three Cuban women had been searched, but that these searches were carried out by matrons.

An enraged Davis exposed this truth in a letter to Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World saying:

“For the benefit of people with unruly imaginations, of whom there seem to be a larger proportion in this country than I had supposed, I will state again that the search of these women was conducted by women and not by men, as I was reported to have said, and as I did not say in my original report of the incident.”

In the end, the New York Journal and Hearst were forced to publish a retraction. But lesson learned? Of course not!

*For background see “War and Response, a Spanish American War Centennial,” and Evan Thomas’ “The War Lovers, Roosevelt, Lodge, Hearst, and the Rush to Empire, 1898,” Little Brown, New Yor, 2010.