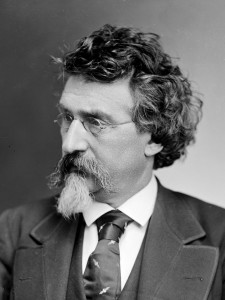

And continuing our discussion of presidential photographs, photographer and grand showman, Mathew Brady (1822 – 1896), photographed eighteen of the nineteen presidents from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley. The only exception was William Henry Harrison, who died in office three years before Brady began his project of photographing presidents and other important people of the day.

Brady started his career studying portrait painting under William Page. At age seventeen Brady moved to New York City, where he met artist Samuel F. Morse, who had just introduced the daguerreotype to America. Brady studied the new art form under Morse. He opened a studio in New York City and in 1845 he began to exhibit portraits of famous Americans, which led to “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans.” In 1849 he opened a second studio in Washington, DC.

Recognize that photography was to the nineteenth century what the IPhone and IPad are to the twenty first. People could not get enough of the new invention. In a sense, Brady was the Steve jobs of the nineteenth century. It was the latest in modern technology, a combination of science and seeming magic. People flocked to have their pictures taken: first as daguerreotypes, then ambrotypes, and finally on glass negatives that we made into albumin prints.

Brady traded a brisk business in popular carte de visites for soldiers during the American Civil War. Brady became obsessed with the idea of photographing the war itself. He received permission to travel to the battle fields from President Lincoln and because emulsions were too slow to photograph war action he photographed Lincoln, famous generals, and hundreds of rotting corpses on the battlefield instead. These now serve as gruesome illustrations for Ken Burns’ haunting documentary “The Civil War.” Brady’s Civil War images are in the tradition of Roger Fenton’s images of the Crimean War a decade earlier. It should also be pointed out that while these pictures are listed under Brady’s studio stamp, he had a team of over twenty photographers in the field including such illustrious names as that of Timothy O’Sullivan, now famous for subsequent pictures of the American West. These photographs brought the war home to clientele in the North and skyrocketed Brady’s fame.

Fame, of course, as history teaches can be a very fleeting thing. Today we owe an enormous debt to Brady. He gave us pictures of presidents and generals we would never otherwise know – capturing forever brief instances of the nineteenth century. But as contemporary interest in the Civil War waned, so did Brady’s fortunes. He went bankrupt and died in poverty. As Ken Burns laments, many of his glass negatives were sold as window glass for green houses and cold frames. They became bleached and crumbled with the century.

There is anew book now

Timothy Sullivan: The king survey photographs (Yale)

These are photographs of the 40th parallel survey whose leader was an eccentric Yankee Clarence King – quite an interesting character.

I saw his shot of the white house ruins , amazing.

Seems his darkroom was converted mule drawn ambulance.

Rajn,

Will have to look that one up, thanks. Sullivan took wonderful photographs, and I really don’t understand why these are consired to be purely technical rather than artistic. Some of them have a wonderful aesthetic appeal.

David