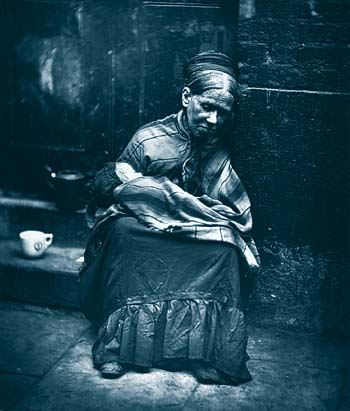

Figure 1 – Jacon Riis, “Children Sleeping in Mulberry Street, 1890,” from the Wikicommons and in the public domain.

Very much the American counterpart of John Thompson as a documenter of life in the urban slums and crusader for social reform was Jacob August Riis (1849 – 1914). We see this so vividly in Figure 1 – “Children Sleeping in Mulberry Street, 1890,” which rivals Thompson’s “The Crawlers,” in its raw and gripping social message. There are three filthy, yet innocent, children, barefoot, and sleeping huddled together above a grating – perhaps some small warmth emanates from beneath. They are below street level, unseen – or if we see them, turn the other way. It is as if they are prematurely buried. They are certainly dead from the perspective of the megalith industrial city – then in its gilded age, that has consumed them.

Riis was a Danish immigrant himself. He had learned of poverty directly, at one point sleeping on a tombstone in New Jersey, his only food apples that fell fortuitously in his path. A carpenter by trade, he became a police reporter and this introduced him to the nameless poverty of the slums of inner New York City, acquainting him with the worst places like Mulberry Street where China Town met Little Italy and where police headquarters was.

Riis tried his hand at sketching to illustrate his exposes, but was no good at draughtsmanship; so he turned to photography instead. Still he was thwarted by the slow lenses and emulsions of the 1880’s. However, Riis learned of the invention by Germans Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke of flash photography. Miether and Gaedicke mixed magnesium with potassium chlorate and antimony sulfide to add stability. The was stuffed in a pistol-like device that fired cartridges. The pistol was both dangerous and threatening to the subject; so Riis soon replaced it with a frying pan in which the powder could be ignited. The process was simple, albeit frightening. Remove the lenscap and ignite the flash. Riis survived and became one of the first Americans to practice flash photography. An eighteen-page article by Riis, entitled How the Other Half Lives, with nineteen of Riis’ photographs rendered as drawings, appeared in the 1889 Christmas edition of the them widely distributed Scribner’s Magazine. This was soon expanded into a book of the same title.

As the images of modern photographer-social reformers testify, Riis work did not eliminate crushing poverty in America. It did however lead to very serious reform and to the development of America’s progressive movement. Progress occurs by degrees. Riis became a life-log friend and colleague of Theodore Roosevelt, himself a campaigner for social reform. Roosevelt said of him; “Jacob Riis, whom I am tempted to call the best American I ever knew, although he was already a young man when he came hither from Denmark”.