My colleague and I were oohing and ahing over the videos of a meteor crashing to Earth in the Chelyabinsk region of the Russian Urals last Friday. We are told that this is a once in a century event; so certainly worthy of being the “iconic image of the week.” People will likely still be watching it a hundred years from now..

It got me thinking of meteors and photographs of meteors and meteorites. Of course, my first thought was a blog on “The first photograph of a meteor.” I was able to learn that the first meteor photograph was taken on a glass plate negative by Ladislaus Weinek director of the Klementinum observatory in Prague on Nov. 27, 1885. However, I was unable to find a copy of this image on the web.

So I combed the cobwebs of my memory for thoughts and visions of meteors. The first is obvious. On June 30, 1908 near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River in what is now Krasnoyarsk Krai, Russia there was a great meteor fall and blast generally referred to as the “Tunguska event.” It is now believed that the meteoroid actually exploded in the air rather than striking the ground. It probably had the force of a ten to fifteen megatons of TNT and knocked down an estimated 80 million trees over an area covering 2,150 square kilometers (830 sq mi). That is a circular diameter of 52km. While there were no “robotic eyes” or surveillance cameras to photograph the event, there are many amazing post blast photographs of the tree fall made by subsequent expeditions.

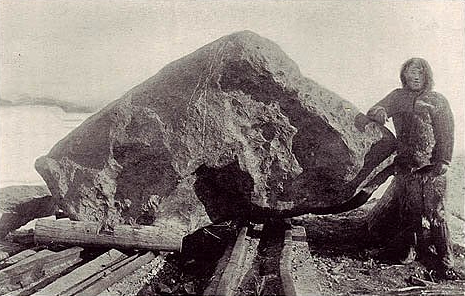

Figure 2 – Robert Peary and tthe Ahnighito Meteorite, 1897, from the Wikicommons and in the public domain.

My strongest memory association with meteorites is as a child being taken by my father to see the great meteorite collection at the Hayden Planetarium in New York City. In 1818, British arctic explorer Sir John Ross was astonished to find that a tribe of Eskimos along Greenland’s western coast possessed spear heads of iron. The Eskimos smartly refused to reveal the source saying only that they came from a mountain of iron, in their language saviksoah. A number of subsequent explorers tried, but failed to find the saviksoah.

By the the turn of the twentieth century Eskimos were actively trading for iron and no longer had the same need for their magic source. An Eskimo named Tallakoteah told explorer Robert Peary that there were three irons: “the woman,” “the dog,” and “the tent. The legend was that there once had been a sewing woman and her dog, who lived together in a tent in the sky. An evil spirit hurled them to the Earth and they landed as great lumps of iron. Tallakoteah led Peary to these stones and, true to imperialist form, he decided to cart them away to New York. This was a Herculean task which ultimately took him several attempts and years. As a child I remember looking with amazement at the tent, or Ahnighito, (also referred to as the Cape York meteorite) where Peary brought it for permanent exhibit at the Hayden Planetarium at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

There are many classic images of Peary collecting this colossal stone in Greenland, transporting it to New York, and then carting it up from the peer to the American Museum. Figure 2 is a example of these images. For a complete telling of the saga of meteorite collection and Peary’s efforts see Douglas Preston’s book, “Dinosaurs in the Attic.”