Figure 1 – a modern replica of a Victorian Zoetrope

Photograph © Andrew Dunn, 5 November 2004.

Website: http://www.andrewdunnphoto.com/ published under Creative Commons attribution license.

The question for today is: “why can we see movies,” or more accurately put: “why can we perceive movies?” You will often see this answered by the phrase “persistence of vision.” Persistence of vision refers to the fact that an afterimage of what you see persists for approximately 1/25th of a second after you see it. This is a purely physical answer akin to saying that every instrument has a measureable response time. It’s been clear, however, for a century, from neurophysiological and neuropsychological studies that persistence of vision is not the cause of motion perception. The bottom line, before we go any further is that the human eye, for many many reasons, some of which we have previously discussed, is not a camera. Perception of image and perception of motion are brain phenomena.

In a sense, this is really all that we need to know. But it is fun to explore this a bit further. The perception of motion appears to be more closely related to what is called the “phi phenomenon” first defined in 1912 by Max Werthheimer (1880-1943), one of the founders of Gestalt psychology.

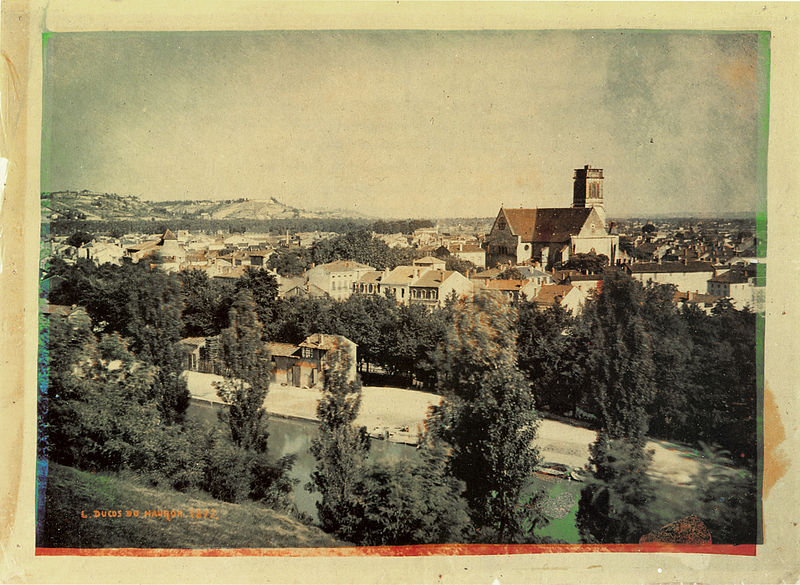

Figure 2 – The Lilac Chaser an example of the phi phenomenon. From the Wikicommons and in the public domain.

The phi phenomenon is often demonstrated to a viewer by projecting two images in succession. The first image might be a ball on the left hand side of the screen. The second image may be a ball on the right hand side of the screen. If you project the two images with sufficient time in between and hold the images for sufficient duration, the viewer sees first a ball on the left and then a ball on the right. However, with certain times in between and certain durations of holding the images steady, the viewer perceives a sensation of motion of the ball between the two sides.The same is true of music. If you play the notes too closely they will blur into a squeal. If you play them too far apart, they become separate and disembodied from the music. I mention this because the music that we launched into space on Voyager may or not be interpretable by some alien civilization that discovers it. That will depend on the way that the alien’s brain operates.

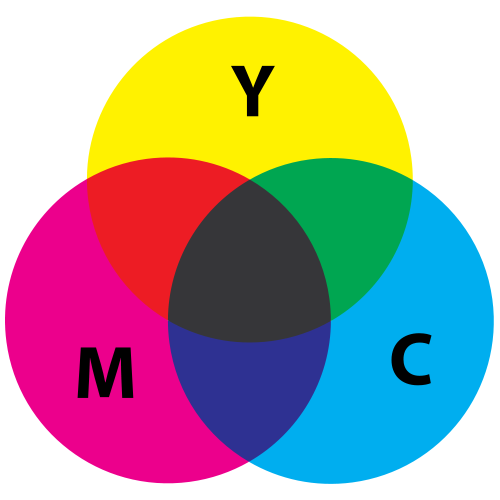

Of course, a great example of this phenomen is that of the zoetrope (see Figure 1), where a rotating drum with a set of images, of for instance a horse running and a lion jumping, is viewed through a slit. Actually, the slits are also rotating. The brain interprets the set of images as the horse running and the lion jumping. This is, needless-to-say just like the successive frames in a movie.

A cool example of the phi phenomenon is shown in Figure 2. It is an optical illusion called the “lilac chaser” and really illustrates the dominance of brain function in image interpretation. In the lilac chaser we observe twelve blurred lilac (aka magenta) disks forming a ring. One of the disks is made to disappear for about 0.1 seconds, then the next about 0.125 seconds later, and so on in a clockwise direction. Now the trick is to stare at the cross in the center, and you may want to click on the image so as to maximize its size.. Don’t cheat keep starring at the cross. When one stares at the cross for about 20 seconds or so, one sees successively three different phenomena. First, a gap appears to run around the ring of magenta disks. This is the so-called beta movement. Second, the gap becomes replaced with a green disk. This is an adaptation of the rods and cones of the retina. The brain is working and interpreting. There is no green disk. Finally, again the brain interpreting, the magenta disks disappear and you have a green disk running around against the grey background.

So the bottom line, or lines, is that:

- the eye is not a camera but part of the eye-brain system

- once the between image timing and the duration of images become fast enough the brain no longer interprets the images as separate

- because of the phi phenomenon there is a sweet spot of image duration and between image timing that the brain will interpret as motion

It is the second of these points that, we will next consider as a further mode of creating additive color from multipile images. And, as I promised yesterday our view of the early twentieth century will no longer be one of subdued black and white, but rather of vivid Technicolor. That will be discussed in tomorrow’s blog.