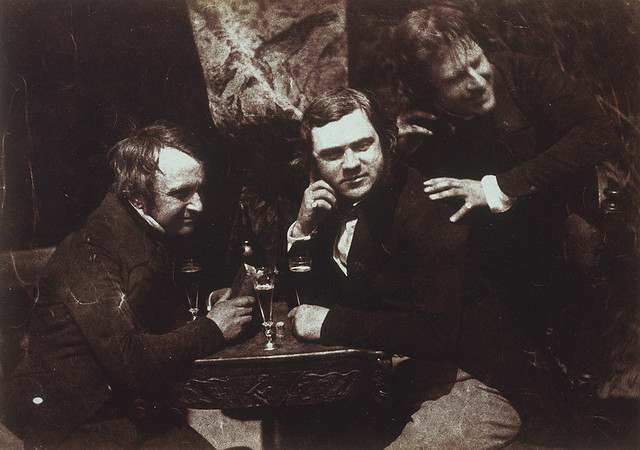

Figure 1 – Edinburgh Ale, James Ballantine, Dr. George Bell, and David Octavious Hill, by Adamson and Hill (1843-1847). From The National Galleries of Scotland Commons via Flickr and the WikimediaCommons.

This past Thursday brought with it the historic vote by the Scottish people to remain joined to the United Kingdom. It got me thinking. Scotland is an amazing and spectacular place. And I was thinking about photographs from the nineteenth century. This lead me to a Google search, and I found myself looking at some of the amazing calotypes of Adamson and Hill. Daguereotypes and calotypes were essentially invented simultaneously. The crisp sharpness of the daguereotype contrasts with the soft sepia tones of the calotype made from paper negatives.

In1843 painter David Octavius Hill formed a partnership with engineer Robert Adamson, creating Scotland’s first photographic studio. Their partnership only lasted four years because of the untimely death of Adamson. But in that brief period their association combined Hill’s artistic sensibity and understanding of composition and lighting with Adamson’s mastery of the scientific and engineering aspects of the craft.

Adamson and Hill produced produced approximately three thousand prints. Photography evolved at the time from deep-rooted artistic traditions and such is the wonderful body of work that they have left us. Images such as the scene from an Edinburgh bar in Figure 1 is not stiff portraiture, but rather is reminiscent of such similar scenes as Peter Bruegel’s “Peasant Dance.” There are, in fact, many such classical paintings – a whole genre of paintings of beer drinking and carousing among all classes.

Watercolorist John Harden, upon first seeing Hill and Adamson’s work in 1843 wrote: “The pictures produced are as Rembrandt’s but improved, so like his style & the oldest & finest masters that doubtless a great progress in Portrait painting & effect must be the consequence.”

There is an interesting connection between Hill and the great Victorian physicist Sir David Brewster. Hill was present at the Disruption Assembly in 1843 when over 450 ministers walked out of the Church of Scotland assembly and established the Free Church of Scotland. Hill wanted to accurately portray the event in a monumental painting. Brewster suggested that Hill use photography to record the likenesses of all the ministers. Brewster had himself experimented with photography, and it was he who introduced Hill to another photography enthusiast Robert Adamson. The painting ( 5′ by 11.3′) was eventually completed in 1866.

As in so many of the masterpieces of the photographic Victorian age in the work of Adamson and Hill we catch a precious glimpse of how life was or how they wished us to perceive it – not necessarily the same thing, of course. In Figure 2 we share through their lens a warm, tender, moody, and perhaps sleepy moment from so very long ago.

Figure2 – Harriet Farnie with Miss Farnie and a Sleeping Puppy by Adamson and Hill (1843-1847) from the Natuion Galleries of Scotland Commons via Flickr and the Wikimediacommons.