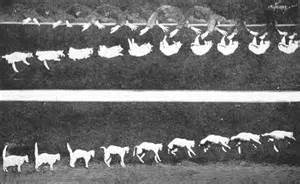

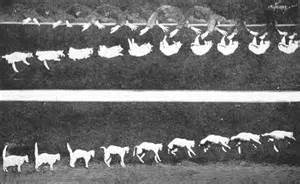

Figure 1 – Falling cat landing on its feet. Multi exposure by Etienn-Jules Marey, 1894. Image from the Wikipedia and in the public domain because of its age.

An ailurophile and reader expressed concern about Schrodinger’s Cat in the Box Paradox and whether any cats had been hurt trying it. Well, to my knowledge it is strictly a thought or Gedankenexperiment and has never been explicitly tried. No physicist would attempt it, as the outcome is painfully certain, that being the whole point of the paradox.

Also evidence suggests that many scientists are true cat lovers and such a thing would be most abhorrent to them. Indeed, Schrödinger in his description of the paradox expresses anquish at the thought of hurting a cat. The other player in the conversation that evolved into the cat in the box paradox was physicist Albert Einstein. Einstein loved all animals but was especially fond of cats. His male cat “Tiger” would get depressed on rainy days. Einstein would talk to Tiger when it rained in an attempt to sooth the feline breast. Einstein is famous for remarking that, “A man has to work so hard so that something of his personality stays alive. A tomcat has it so easy, he has only to spray and his presence is there for years on rainy days.” Sir Isaac Newton, the founder of modern physics, was also a great cat lover and is credited with the invention of the cat door flap.

My favorite among scientist cat lovers however, was Sir Thomas Huxley. His son relates in his biography of his father how if he found a cat asleep on his favorite chair, he would ask one of his children to move it. In a passionate letter to his daughter, Huxley defends a scratchy kitten who his wife has banned from the drawing room and beseeches his youngest daughter Ethel to intercede with mama:

“I wish you would write seriously to M. She is not behaving well to Oliver. I have seen handsomer kittens, but few more lively and energetically destructive. Just now he scratched away at something that M says cost 13s. 6d. a yard, and reduced more or less of it to combings.M therefore excludes him from the diningroom, and from all those opportunities of higher education which he would naturally have in my house.I have argued that it is as immoral to place 13s. 6d. a yardnesses within reach of kittens as to hang bracelets and diamond rings in the front garden. But in vain. Oliver is banished, and the protector (not Oliver) is sat upon. In truth and justice aid your Pa.”

So I believe that we can safely say that no cats were harmed in the production of the Schrödinger’s Cat Paradox.

Cats did, needless-to-say, figure vigorously in the resolution of another nineteen century conundrum – namely whether and how a cat manages to land on his feet when dropped upside down. STOP!!! DO NOT TRY THIS AT HOME!!! NOT ALL CATS ARE EQUALLY AGILE. The problem was solved by with the multiexposure photograph from 1894 by Étienne-Jules Marey shown in Figure 1 and also by his 1890 video. Actually Markey’s work only showed the mechanics of the fall. A full explanation had to wait until the late 1960’s. Marey was a contemporary of Muybridge and a pioneer in understanding and photographing human and animal motion.

The key to the cat’s dilemma, (actually it is not a dilemma for the cat, who because of her righting reflex knows just what she needs to do)see Figure 2, is that when held upside down she has no angular momentum, meaning that she is not rotating. Angular momentum must be conserved. So it must remain zero. But the cat needs to turn or she will crash on his back.

The cat accomplishes this by cleverly rotating the two halves of its body in opposite directions, thus maintaining zero angular momentum. I have looked at a number of sites on the web where the rotating cat problem is explained. The best is this one and I cannot do better myself. Let me just give a little background. Stand and try to twist your torso, you will notice that your legs will push against the ground and will try to twist your lower body in the opposite direction. If you are in free fall there is nothing to push off of. You can twist your torso in one direction but only if you twist your lower body in the opposite direction. Angular momentum stays as zero, but it doesn’t help at all as you twist like a bread tie. That is until you remember the ice skater who brings her arms in to rotate faster. Watch the video. The cat pulls in her front paws to speed the turning of her torso while at the same time extends her rear paws to slow the counter rotation of her lower body. She then reverses the process. It’s really cool physics and wonderfully revealed to the world by stop action photography.