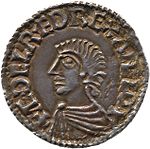

Figure 1 – Charles Dodgson’s “Charles Dodgson “Alice Liddell as a beggar-maid from the story of Cophetua, 1858,” from the Wikipedia and in the public domain.

Today’s favorite photograph is Charles Dodgson‘s (1832-1898) ” Alice Liddell (1852-1934) as a beggar-maid from the story of Cophetua, 1858.” It contrasts, so similar yet so different, from the image of yesterday, Roman Vishniac’s “The only flowers of her youth, 1938.” One is imagined the other real.

Dodgson is, of course, the real name of Lewis Carroll the author of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking Glass.” And Alice Liddell is the namesake of the stories. They were written for and dedicated to her.

It is difficult to look at one of Dodgson’s photographs of young girls without the more sordid aspects of these relationships coming to mind. And, as I have said before, such too is the case for Dodgson’s contemporary Oscar Reijlander (1813-1875). However, to my mind this is really a wonderfully playful and sensitive image.

It is an image of emergent beauty and coming of age into womanhood. So what about this Cophetua person? Cophetua was a mythical African king who lacked sexual attraction to women. One day he is looking out his palace window, when he sees a young beggar, named Penelophon, who is suffering for her lack of clothes. It is “love at first sight!” Oy! So Cophetua vows that he will have this beggar as his wife or he will commit suicide. Cophetua scatters a path of coins to attract Penelophon and when she approaches he informs her that she is to be his wife. Now how can she refuse this offer? Uhh! The details of this story, unfortunately, make it even harder to ignore the more sordid side of Dodgson’s attraction. Did I mention that Alice Liddell was six at the time of this photograph?

Needless-to-say a key appealing element of this image is its historic association, who the photographer is and who the subject is. Beyond that the enigmatic expression on Alice’s face is charming, as is the three quarter view with her eyes towards the camera. The way in which her hand is cupped to tell the story of Penelophon is such a simple yet compelling gesture. The smudges of dirt on her legs add detail, and finally the lighting is wonderfully dramatic. This picture reaches out to us across time from what was only the second decade of photography.