Figure 1 – A compound schizochroal eye of the trilobite Phacops rana, eye dimensions 8mm across by 5.5mm high, found near Sylvania, Ohio, USA, from the Devonian, from the Wikimedia Commons image by Dwergenpaartje and in the public domain under creative commons license.

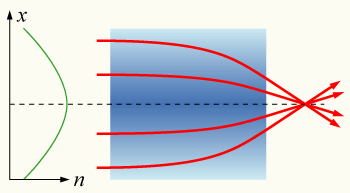

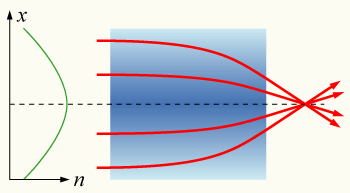

On Wednesday we discussed how to correct a lens for spherical aberration: you can use an aspheric shape, you can add a second compensating lens, ideally of a different index of refraction, and you can use a single lens where you grade the index of refraction. The last of these solutions is the very high tech GRIN lens. The concept of the GRIN lens is illustrated in Figure 2. The shape of the lens is a simple cylinder. However, because the index of refraction changes radially with the kind of parabolic distribution shown on the left, the lens focuses light and corrects for spherical aberration just as if it had a curved surface.

Figure 1 – Schematic of a GRIN lens. Left – the radial distribution of the index of refraction, Right – the cylindrical GRIN lens. From the Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain under creative commons license.

A GRIN lens is not the kind of thing that you expect to see in a prehistoric compound eye. However, both all three approaches, used today by optical engineers to correct for spherical aberration were employed by nature hundreds of millions of years ago in the construction of trilobite eyes.

Trilobites are a well-known fossil group of extinct marine arthropods that had three part bodies. They first appeared in the early Cambrian (521 million years ago), and roamed the seas for the next 270 million years, becoming extinct 250 million years ago. Those numbers are kind of mind boggling.

Unlike the eyes of modern arthropods which use protein-based lenses, the lens material trilobites utilized was the mineral calcite. As a result, they are remarkably preserved after hundreds of millions of years and ready for study. Species such as Crozonaspis used an aspheric lens design that is remarkably similar to that developed by Rene Descartes in the seventeenth century. Crozonaspis further corrected its lens by addition of an an intralensar body, essentially a second lens element made of a material with a different index of refraction. Most remarkable are the lenses of Phacops rana, see Figure 1 which are actually GRIN lenses, where the calcite, or calcium carbonate, is doped with magnesium carbonate.

It is a remarkable story – complex lens designs created by nature 250 plus million years before Descartes. The two significant limitations of trilobite eyes, indeed of all compound eyes, is the lack of a means to change focus and the lack of resolution. This ability to change the eye’s focus is referred to as “adaptation” for human eyes and was first explain by the great British polymath Thomas Young(1773-1829). In humans this change of focus is accomplished by bending of the lens. It is, of course, what we do with a camera lens by changing the distance between lens elements or more simply by changing the lens’ distance from the photosensor. Resolution, as we have seen is largely matter of f-number.