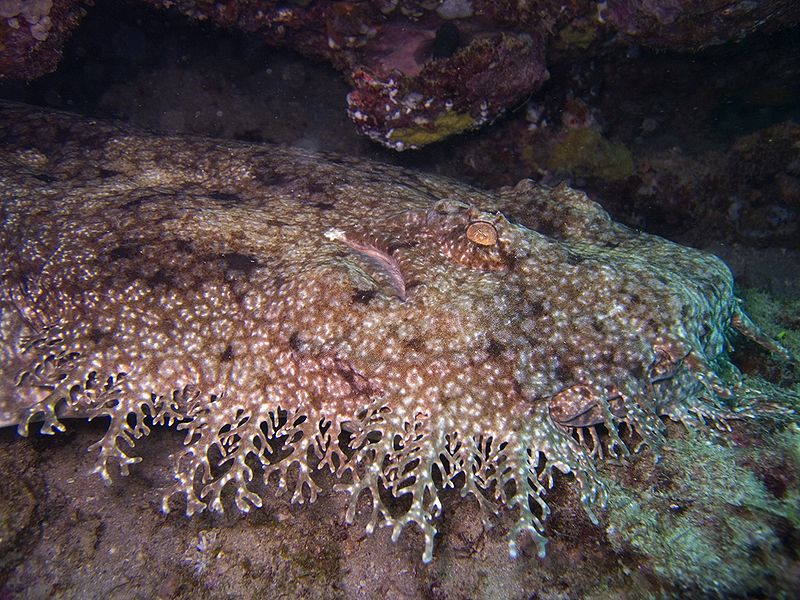

Figure 1 – Tasseled wobbegong shark, from the Wikimedia Commons, original image by Jon Hanson and reproduced under creative commons license.

Well, it’s early August. The great white sharks are following the seals to Cape Cod, and a day barely goes by without a reported sighting. The official Shark Week is a tradition started in 1987 by the Discovery Channel. Other TV stations seem to follow suit with all the great viscerally terrifying movies like: “Jaws”, “Jaws 2,” “Jaws 3,” “Deep Blue Sea“ (my personal favorite shark movie), and “Open Water.” Just stay out of the water people!

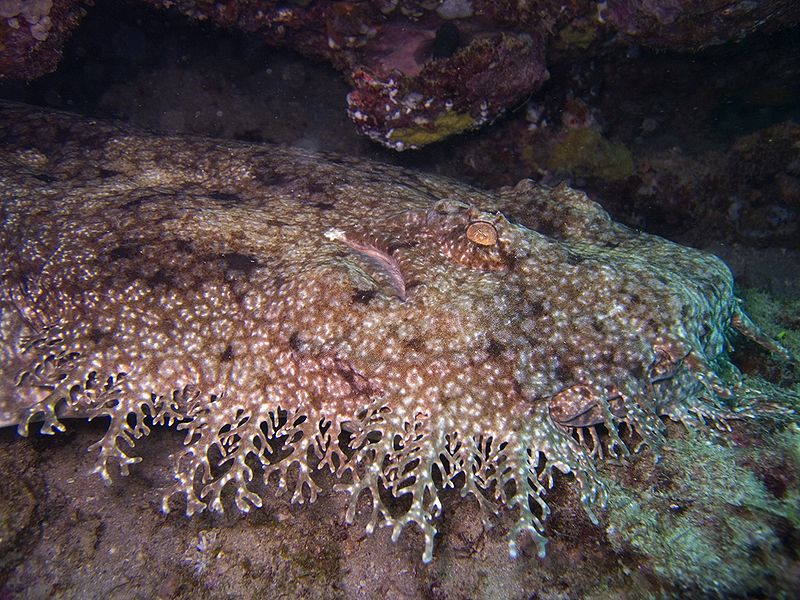

Anyway, and following up on yesterday’s blog about the Whale Shark, I’d like to deviate just a tad from the purely photographic and talk about the Wobbegong (Orectolobae) (see Figure 1). I am inspired in this by a reader who posted Figure 1 on her Facebook page. Wobbegongs are bottom-dwelling sharks, mostly to be found in the pacific just cruising around and resting on the sea floor. Most wobbegongs have a maximum length of 1.25 metres (4.1 ft) or less. However, the spotted wobbegong (see Figure 2), Orectolobus maculatus, can grow to lengths approaching ten feet.

The fellow shown in Figure 1 is a tassled wobbegong (Eucrossorhinus dasypogon). It is a species of carpet shark and kind of does look like a carpet. It can be found in shallow coral reefs off northern Australia, New Guinea, and adjacent islands and can grow to about six feet. It’s fringed dermal flaps and coloration provide camouflage that enables it to trap and ensare small fishes that take it for a pile of seaweed.

While tasseled wobbegongs will bite the foot that steps on them, the fate of wobbegongs is similar that of many other shark species. They are eaten by humans. Their flesh is called flake and consumed by humans in Australia, and their skin is prized as a source of leather.

And you thought that this post was going to be about a fictional lake in Minnesota.

Figure 2 – The spotted wobbegong, image from the Wikimedia Commons, original image (c) 2005 Richard Ling and reproduced under creative commons license.