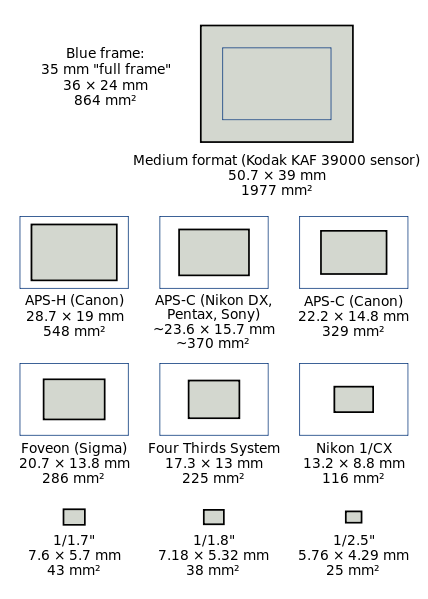

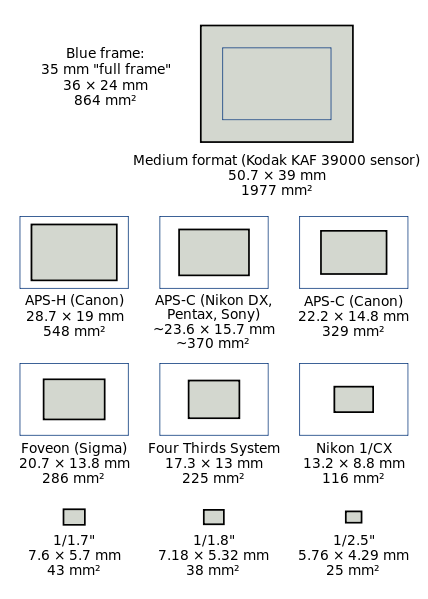

Figure 1 – DSLR camera sensor formats compared. Image from the Wikimediacommons and in the public domain.

I have been dealing with a lens problem over the last few weeks, and as a result, I have been sorting out in my mind the relative advantages between the APS-C and full frame sensor cameras. At the risk of becoming soporific, the story begins with where does that pesky multiplication factor come from. But a first question: what am I talking about? If your DSLR camera (refer to Figure 1)has a full frame sensor it is a 26 mm X 36 mm or 864 mm2, which means that it is the same size as 35 mm film. However, if your DSLR has an APS-C sensor it is smaller, 15.7mm x 23.6 mm or 370 mm2 for Nikon and 14.8mm x 22.2mm for Canon or 329 mm2. Now suppose you put a standard lens (one designed for the full frame format) on the camera. Your APS-C sensor will only image the center of the field. Your image will appear magnified relative to the full frame format by a factor of 36/23.6 = 1.53 for Nikon and 36/22.2 = 1.62 for Canon. There is your magic multiplication factor.

Image magnification is determined by focal length. For example, a 100 mm lens magnifies two-fold compared to a 50 mm lens. As a result whatever the true focal length of the lens is, you need to multiply by this multiplication factor to get the equivalent focal length for an APS-C camera. For instance, if you are using a Canon 18mm to 55 mm zoom lens, it is equivalent on a APS-C camera, such as the Canon T2i, to a 29 mm to 89 mm zoom.

It is logical to ask which is better? And if you are a regular reader of this blog then you know that I am going to obsess about two factors: image sharpness and image dynamic range. Given that, and before we can discuss relative advantages, we have to consider one more technical point. Suppose that you start with the APS-C sensor and you want to make it bigger, indeed you want to make it full frame, then you can do this in one of two ways: you can make the pixels bigger and keep the same number of pixels or you can keep the size of the pixels the same and just add more of them. This is not a minor point, as we shall see.

Canon’s full frame cameras, for example the EOS 5D and the EOS 6D have approximately 22 Mp “resolution.” Compare this to their APS-C cameras at 18 Mp “resolution.” This means that there are about 22 % more pixels or about 10 % more on a side. Basically, this means that the pixels are bigger, but that the number doesn’t change by much. Nikon kind of goes both ways. Their APS-C cameras have around 24.1 Mp. Their full frame cameras come in two flavors. The D800 has 36.3 Mp, meaning 50 % more pixels or 23 % more on a side, while their D600 series has a full frame sensor with 24.3 Mp, meaning no change in the number of pixels.

Advantage APS-C – Price

The big advantage of the APS-C sensor is that it is cheaper to manufacture. The reason for this is that the larger a sensor you try to manufacture there more likely you are to have a flaw. Flaws were acceptable back in the Jurassic, when I was a lad, and we were first using cooled-CCD cameras for scientific measurements. In the consumer market, this is totally unacceptable. There can be as much as a 20 fold increased cost associated with making a full frame, as opposed to APS-C, sensor. This is reflected in the increased cost of full frame DSLR cameras, approximately five to six fold.

Advantage full frame dynamic range and signal to noise

If you have a larger sensor then its well depth, the number of photoelectrons that it can hold increases as the area. So roughly speaking, if you hold the number of pixels constant and increase the area of the pixel by (1.5)2 or 2.25, you gain over a two-fold increase in your camera’s dynamic range. Also the more electrons the better the signal to noise. This is going to help you out in low light images, but only by about a factor of about two or one f-stop.

What about image sharpness

The story with sharpness is a tricky one. First, of all most lenses perform best, from a sharpness or modulation transfer function point (MTF) of view, at or near their centers. It is the edges that are hard to get sharp. I am in love with my Canon EF 70-200mm f/4L USM Lens. This lens has an outstanding MTF. Couple that with my APS-C sensor and the performance is just amazing! In addition, it is easier for lens manufacturers to design high quality lenses for a smaller sensors, and again easier translates to price.

Last October we spoke extensively about photographic image resolution and I showed you that the resolution of a camera lens is 1.22 x wavelength of the light x f-number. For green light this is about four microns. We also showed that for good DSLRs this is about equal to the interpixel distance (for a 18 Mp APS-C sensor). Recognize that the focal length of the lens comes in because the f-number is the focal length divided by the aperture and that this refers to the true focal length. So if you keep the number of pixels the same going to full frame you will lose a bit in resolution or sharpness. But say that you increase the number of pixels enough to keep the interpixel distance the same (that was 2.25 fold in the previous example), then your resolution or sharpness will be the same. However, if the resolution is the same then when you print or project your image on a computer screen you will have more pixels.

Last fall we discussed in detail how many pixels you need as a function of print size. What we found there is that 300 pixels per inch is more than sufficient and this means that today’s APS-C sensors certainly provide sufficient sharpness for a crisp 12” x 18” image.

My bottom line

When I started writing today’s blog I was afraid of being boring (I have no doubt succeeded in that), but at least I thought the subject pretty straight-forward – 1100 words later, no so much! You can see that there are advantages both ways, which makes the choice ambiguous. My bottom line is that for the kinds of photography that I do and the print sizes that I am aiming for there is no real value to going full frame. Affordability is very key, since everyone has limits on how much they can spend on equipment. The ability to add another lens to my photographic arsenal, outweighs the minor disadvantages of the APS-C.