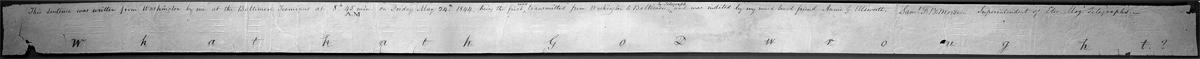

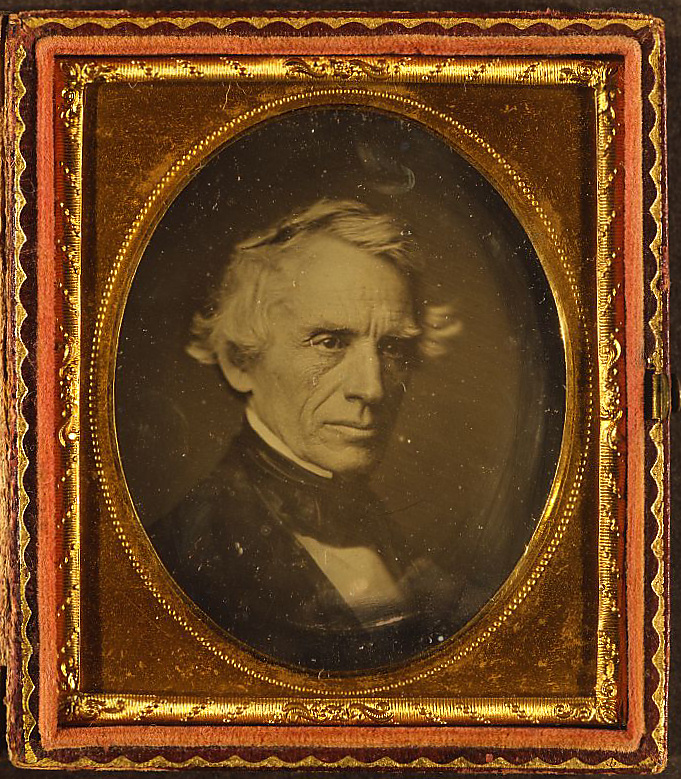

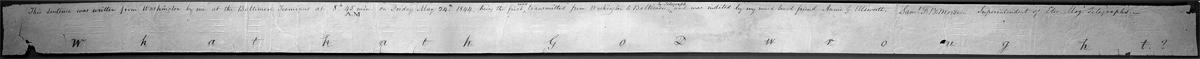

First Telegraph Message sent between Washington, DC and Baltimore, MD on May 24, 1844 by Samuel Morse. “What hath God wrought?” From the Wikimediacommons and in the public domain.

If you have a picture that you want to transmit to another place, computer, or person you’ve got to decide whether you want to do that in an analogue or a digital mode. More accurately the nature of the communication system tends to dictate the mode. So it is useful to consider what we mean by these two terms.

Suppose that you have a signal like a voltage. Let’s say it’s between 0 and 1 Volt. if analogue, this voltage can take on any value between 0 and 1. A digital voltage is broken down into a set of discrete values. This might be in steps of 0.01 V or some other division, like some power of two. For instance, when we talk about the intensity level of a pixel for a digital camera, this is a discrete digital number.

Most electronic devices today move back and forth between the analogue and digital world. If you remember our discussion of how a CCD camera works, we spoke about the fact that each pixel adds up light induced electrons to create a voltage. When the chip is read that voltage passes through an analogue to digital converter, that converts the voltage to a discrete digitized signal. Today once you’re digital, you tend to stay digital. The numbers are handled digitally in your computer, by your image processing software, and then displayed digitally. In the age of say television with so called cathode ray tubes, everything stayed analogue.

This is the basics of the analogue vs. digital world, But if you really think about the case of our CCD pixel, it never was really analogue. The voltage was really a discrete number of electrons. It was really digital to begin with. In fact most physical signals are based upon inherently discrete processes.

The simplest digital system is the two state or binary system. The state is on or off zero or one. That’s how our modern computers work, ultimately in binary. Multiple zero or one bits are required to express a given number. For instance, the number 13 is 1 times 8 (or 2^3) plus 1 times four (or 2^2) plus 0 times two (or 2^1) plus 1 times one (or 2^0). This is usually written as 1101 in so-called binary. This binary number has a eights column, a fours column, a twos column, and a ones column. This is just like our usual tens power counting system has a hundreds, a tens, and a ones column. So the number 13 in a base ten system is 1 times ten plus 3 times one, or 13.

There are other digital systems. If you think about our English alphabet, there are 26 letters. So any word can be expressed by a string of these 26 values. If you’ve heard about quantum computing that intrinsically is a base four system where any number can be expressed as a series of numbers or columns, where each value is 0,1,2 or 3.

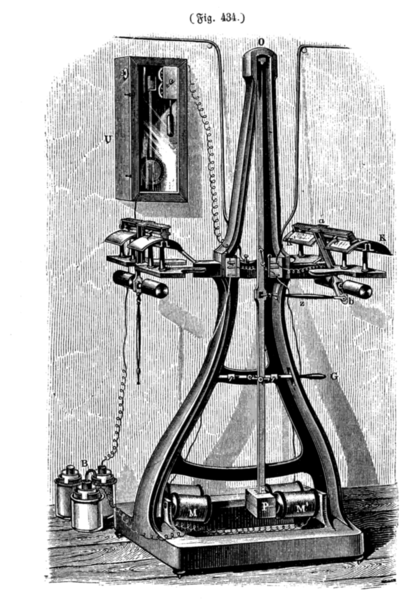

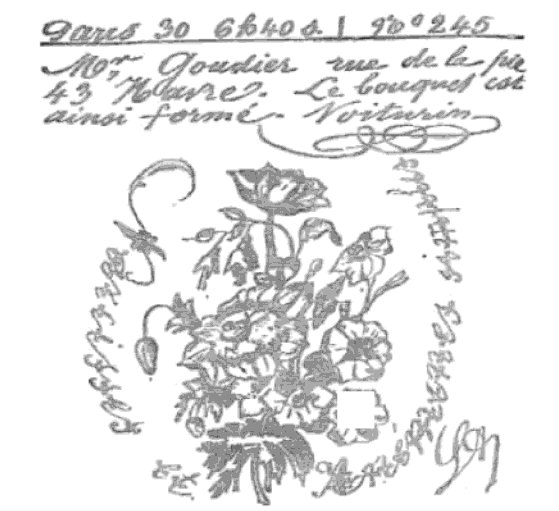

Morse code is very interesting. Remember telegraphy was the first data transmission system; so you would have thought that it would be analogue. But, when Morse developed his code. He expressed everything as dots and dashes. He used time or duration as a second dimension. So at any point the signal is either off, on for a short while, or on for a long while. In a sense this is equivalent to a three state system, where everything is a string of 0’s, 1’s, and 2’s. All of this can be very clearly seen in the world’s first telegram send by Samuel F. B. Morse between Washington, DC and Baltimore, MD on May 24, 1844, “What hath God wrought?” If you blow the image up you can clearly see the dots, dashes, and empty spaces recorded on the paper strip as well as Morse’s translation of it below. The world’s first internet, the telegraphy network, was a digital one.