Yesterday, I wrote about images of the Challenger disaster and how the event, and by connection the images of the event, became sacred. Not surprisingly, sacred memes and their connected images are a quintessential element of human culture. The example given spoke directly of God. But it is very important to point out that while the sacred as it relates to religion and numinous deities is certainly a widespread class of cultural memes, there are other memes that we hold sacred. We hold family sacred. We hold country sacred. We hold our political systems and institutions sacred. We hold our cultural traditions, our literature and our legends all sacred. These are all memes, and whenever an image resonates with a sacred meme it strikes a chord with which we relate very deeply.

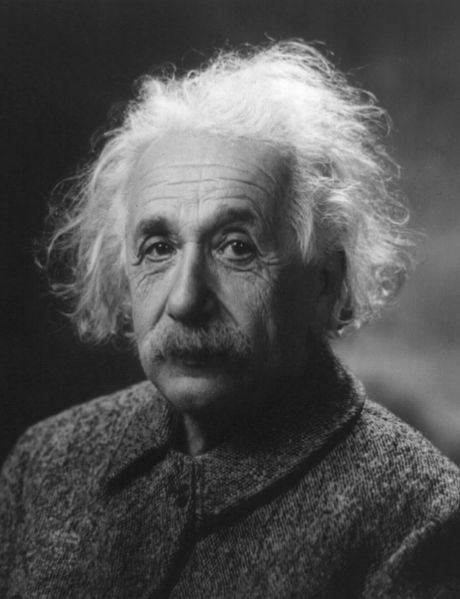

Our religions seek to explain our place in the universe. And, in a sense, anything that serves the same role we also hold sacred. If we are overwhelmed by the beauty of nature, we hold that sacred. If we stand in respectful awe at ancestors who defended our nation and way of life, we hold them sacred. In the past couple of weeks, I showed images of several scientific greats: the Curies, Einstein, and Tesla. All of these individuals sought to explain the place of men and women in the universe, and in a very real sense we hold them sacred.

The role of photography in all of this is defining. Look at the images of these people, we can almost touch them, and the hair may rise on the back of our necks. But in all cases these people are gone from us, replaced, extended, and redefined by palpable and cogent memes.

It is significant to point out that the sacred is culturally specific. In his magnum opus “The Masks of God,” Joseph Campbell points out that God does not appear to the native American, in the sweat lodge, in the robes of Jesus, but rather in the form of an eagle. But we believe that the context is universal.

I have seen this mask effect first hand. I was once in a museum looking at a painting of a woman in a shower of gold coins. It seemed very strange, and I read the label “Zeus Seducing Danaë in a Shower of Gold.” We hold very dear and sacred the myths of the Greeks and Roman. Judging by our art, it is almost as if they are part of our religions. But this image, this meme, so clear in the renaissance was lost to me. The story is from Ovid’s “The Legend of Danaë.” At least I recalled that she was the mother of Perseus set adrift in a box (like the Meme of Moses). When Acrisius consulted the oracle(ever up to mischief) he was told that he would have a daughter, whose son would grow up to kill him. Now that was a big “uh oh” in Greek mythology, otherwise ever ripe with matricide, infanticide, and patricide. So he cast his daughter Danaë in a subterranean dungeon so that she would not meet any suitable men. So along comes Zeus, who to impress the maid appears as a shower of gold coins.

Another example of meme lost or meme mutated is when we attempt today to read Shakespeare. Hamlet says: “Time is out of joint. Oh cursed spite, that ever I was born to set it right.” We have come to believe in an ever rapidly changing world. To the Elizabethans the universe was static and unchanging. Hit them with a comet and watch out. Hamlet knows that to mess up the order of the world put you in serious trouble with the big guy upstairs. However, his uncle has upset the world order, and it is Hamlet’s responsibility to fix it. But this very act of fixing it, he is messing it up again. It’s kind of a Shakespearean “Catch 22.”

What we are ever seeking is to understand our place in the universe and in that context, we are ever seeking the sacred and images that resonate with sacred memes. Let’s be clear what we mean by resonate. You move a bow across the a string on a cello. The bow attempts to impart all sorts of tones to the string, but they are almost all damped out. The bow may even attempt to get the string to vibrate laterally, which it refuses to do. All of the frequencies or tones fall victim to the damping forces except for the very few that have just the right frequencies (those that have nodes on either side of the string). These are the resonances: pure and clear and loud. So too, images that resonate with sacred memes are the ones that effect us the most strongly.

And while we seek and gravitate towards those memes that are particular and defining of our own individual culture, we search forever for the universal memes, those that define what it fundamentally means to be human. Some years ago I visited Chartres Cathedral and I was amazed to see a stained glass window depicting a man with a tree growing out of his loins. It struck me at the time that this was an image depicting Vishnu living in a lotus blossom that grew out of the navel of Brahma. Each night the lotus would close up. Each morning it would open up again. A life had passed. I wondered why was this Hindu meme to be found at this holy christian site. Of course, that wasn’t it. It is foretold in Isaiah:

“11:1 And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse, and a Branch shall grow out of his roots:

11:2 And the spirit of the LORD shall rest upon him, the spirit of wisdom and understanding, the spirit of counsel and might, the spirit of knowledge and of the fear of the LORD.”

This is the lineage of the Christ. But you see, the meme of the world tree the central axis of the world is one of those universal memes.

The Cathedral of Chartres is one of those truly amazing universally sacred places. Needless-to-say, I didn’t take any photographs that day. If I had been a better photographer, I might have found a way resonate my images with all of the sacred universal memes that define that site. I was in awe. And the great Hebraic scholar Joshua Abraham Heschel (1907-1972) has taught us to look for the sacred in the awe.