As promised, today I want to discuss the darker side of fashion photography. And also as promised, I’m going to get up on my high horse.

The fashion industry, and by default much of fashion photography, is selling sex. Ok, there’s nothing wrong with sex. Often this kind of fashion photography is designed to provoke. We are bombarded with women’s breasts, women’s falsies, men in women’s dresses, and both men and women’s genitalia. This world is a crotch fest.

Ok, at most levels even that doesn’t bother me, and it is certainly an improvement over the fashion magazines of the seventies and eighties when there were invariably women about to be dismembered by doberman pinschers. I’m not quite sure what they were selling then – certainly not the much maligned doberman. Now we only have Tom Brady being attacked by a doberman or wearing its collar.

There is taste and there is bad taste. Yes, it’s a relative thing, and yes I’m even ready to forgive bad taste. I’m ready to accept the fact that bad taste can sell and that’s ultimately and unfortunately what it’s all about.

But the relativity and commerciality doesn’t alter the fact that you know when the limit’s been crossed. It’s been crossed when things get degrading and therein lies the fundamental problem.

I’m a child of the sixties and the seventies. Those were very turbulent times, and in the safety of retrospection, exciting times. A great off-shoot of those times was the women’s movement. We’ve seen women make great strides since then, and we’ve watched them take it all for granted and slip perilously backwards in the intervening years.

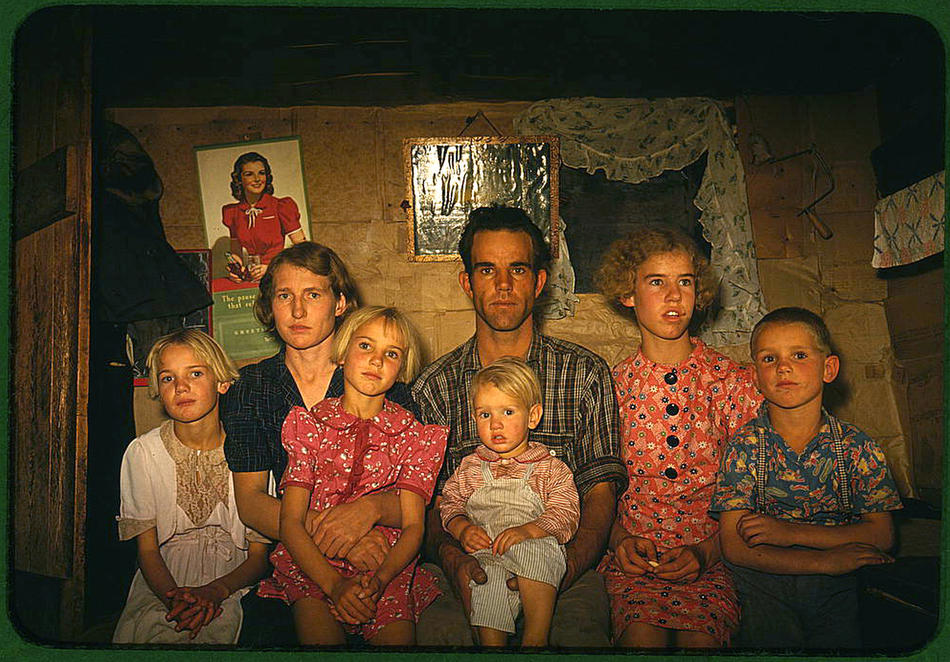

Frankly, there is nothing more beautiful than a beautiful woman in beautiful clothes. But the darker side of that industry, and the photographs that promote Darth Vader’s view, objectivize and exploit women. Worse many of the women involved are really young girls, essentially children. And young girls seek to emulate this view of themselves, thus perpetuating the worst of this mindset.

It is perhaps the ultimate irony to see a young business woman in the airport studiously reading one of the glamor and fashion magazines. In so doing she has become complicit in the world that she claims to hate. That, one man’s opinion, is what troubles me about this darker side of photography.