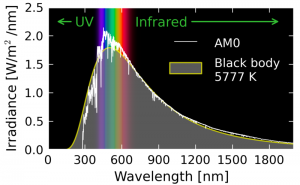

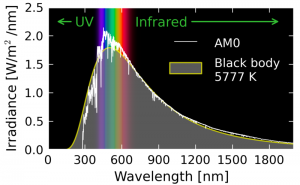

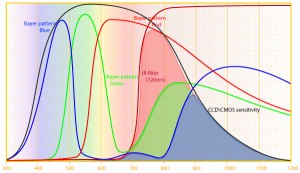

Figure 1 – The solar spectrum, By Danmichaelo (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In researching my last blog on the Infrared Photography of Davide D’Angelo, I discovered that there was a bit of a controversy about whether infrared photography should be possible with digital cameras that are “infrared filtered.” So I thought that I would explore that here, for those of you who want to try it for youselves.

OK, so for starters, let’s look at the spectrum of sunlight (see Figure1). The bottom line from this is that there is a lot of light in the near infrared (700 – 950 nm).

Next, the bar is set by classical, i.e. film-based, infrared photography. What is, or was the response of such films? Let’s look at the spectral response of Kodak High-speed HIE Infrared Film. This pretty clearly tells us that we are, or were, looking at the spectral region between 700 and 950 nm.

So what we need to do is filter out the visible, maybe allowing a little deep red, using what’s referred to as a long-pass filter. Let’s look at the spectra of some of these filters. We see that a Wratten number 87 or 88 will do the job for us. Note the Wratten number 89B, which is the Hoya 72 filter. It allows a bit more red to pass, but as we shall see may be the compromise you need to get this to work on your digital camera.

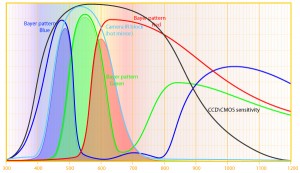

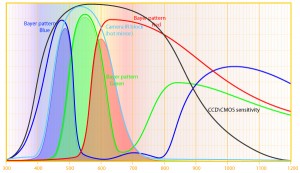

Figure 2 – Spectral response of a standard digital camera CCD/CMOS by http://www,ir-photo.net under creative commons license.

Finally, we need to consider the spectral response of digital cameras. What we call a pixel on the sensor of digital cameras is actually a small pattern or array of pixels divided into three groups: those with a micro-blue filter over them, those with a micro-green filter over them, and those with a micro-red filter over them. The sensor is then filtered in two more ways. There is a filter to remove UV light and there is a filter to remove infrared light.

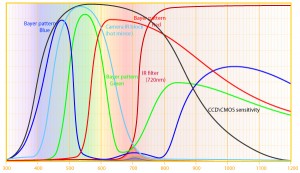

Figure 3 – Spectral response of a standard CCD/CMOS digital camera with a a Hoya 72, Wratten 89B, filter by http”//www.ir-photo.net under creative commons license.

The net effect of all of this is shown in Figure 2. The shaded blue, green, and red areas, referred to as Bayer patterns, are the individual color sensor elements. The blue, green, and red solid lines show how the responses of these elements would be in the absence of the “extra” filtration.

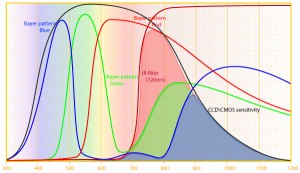

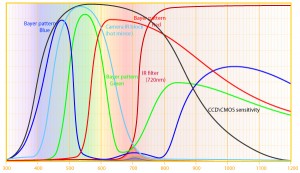

Figure 4 – Spectral sensitivity of IR converted digital camera (CCD/CMOS) camera used in conjunction with a Hoya 72, Wratten 89B, filter by http://www.ir-photo.net under creative commons license.

Next (Figure 3) let’s add a Hoya 72 filter. Note the little shaded area that ranges from about 650 to 775 nm. That is the IR sensitivity of such a camera. It looks pathetic, but it will give you images provided you put your camera on a tripod and accept the necessary long exposures that you will need.

You can, however, have your camera modified (typical cost $200 to $300 depending on camera, in 2012), which entails removal of the IR cut-off filter. Some examples of these services are LifePixel, and Digital Silver Imaging, and This is shown in Figure 4 and gives you back all of the beautiful infrared sensitivity that is intrinsic to the CCD and CMOS detectors. Indeed, this sensitivity extend well beyond 1200 nm, greatly exceeding that of Kodak HIE film.

One important word of additional caution is that the focus changes. Some lens have specially marked lines on the lens barrel to indicate where the IR will be in focus. In the absence of this, you are going to have to experiment to locate this line.