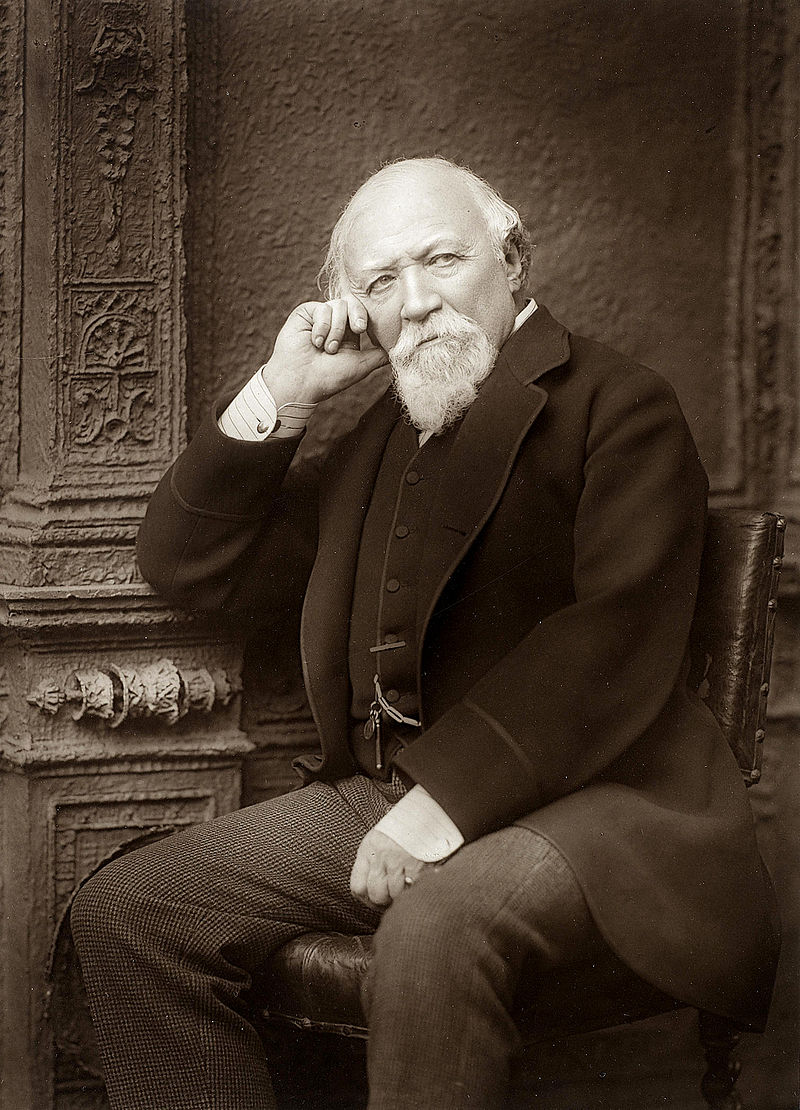

Figure 1 – The first newspaper photograph of future president Richard M. Nixon (second from right), Los Angeles Herald, 1916, public domain.

“No man knows the value of innocence and integrity but he who has lost them.”

I have entitled today’s blog “The fall from innocence.” The phrase has a kind of religious ring to it, as if to connote The Fallen Angels or Man’s Fall from Grace and the Garden of Eden. Today marks the 45th anniversary of the Watergate Break-in, when several burglars, ultimately linked to the President of the United States, were arrested for breaking-in to the offices of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate complex in Washington, D.C. – the President of the United States connected with criminal activities, cover-up, and obstruction of justice. It precipitated a constitutional crisis and, arguably, our democracy proved stronger for it.

For those of us who witnessed the events of the scandal evolve, moment by moment, on our television sets, who read it, day by day, in our newspapers and weekly magazines the very word “Watergate” fills or minds with so many memetic images. I pondered long and hard as to which photograph of the day would be best to illustrate and commemorate the event. I settled in the end with the unfamiliar, but poignant image of Figure 1, which I think truly shows the tragedy of Watergate, because ultimately tragedies are personal. It is a picture taken by a staff photographer for the Los Angeles Herald in 1916, showing a uwoman with three children each contributing a nickel to aid orphans of the First World War – three angelic innocent faces, performing an act of charity and kindness. The child in the middle is then three-year old Richard M. Nixon, who credited it as the first time that his face appeared in the papers.

It would appear many more times. But what is of interest to me is how someone falls from innocence and grace to infamy. It is one of the great mysteries of how time treats us. We may truly wonder about this, and to me that is what the photograph connotes. In the words of American Congregationalist Theologist Lyman Abbott (1835-1922):