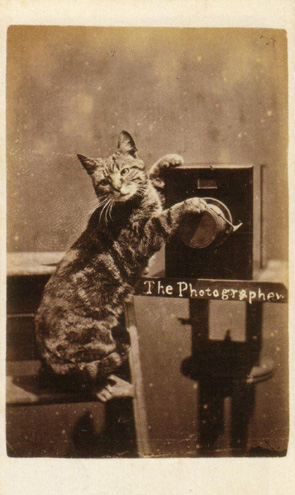

Figure 1 – Possibly the earliest photograph of a cat. From the Houghton Library at Harvard University and in the public domain in the United States because of its age.

All of this dog and cat stuff is bringing us awfully close to “cute and cuddly animal pictures,” and I don’t want to be accused of that. So perhaps it is time to close this particular discussion with the image of Figure 1 of a daguerreotype showing a kitten in Harvard University’s Houghton Library.

According to Harvard this may, in fact be, the earliest cat photograph ever taken, or at least existing. It is rather blurred unfortunately; so the inherent cuteness of this long ago kitty is not really clear. And since all we can really say is that this image dates from somewhere between 1840 and 1860, it may well have competitors for “first” from the many daguerreotypes of “child with cat,” “woman with cat,” and “man with cat.”

While we ailurophiles and people dodging doggie doo-doo on the sidewalk know the answer, ultimately, photography is mute on the subject of which is the better or nobler pet, a cat or a dog. Imagine that you live in ancient Egypt in a home potentially filled with scorpions, rats, and snakes. It was your cat that protected you ever so fiercely. The lioness goddess Bastet was fiercely protective and warlike. As a result cats were sacred to Bast and they were mummified. Herodotus described how, when there was a fire, people would guard it to be certain that no cat ran into the flame. This does not speak to a great familiarity with the behavior of cats. When a cat died, the household would go into mourning just like for a human relative. They would often shave their eyebrows to signify their loss. Diodorus Siculus, described witnessing a Roman accidentally kill an Egyptian cat around 60 BC. An angry mob quickly gathered and mete out the required penalty of death for such an offense.

Many people claim that cats have never really gotten over being worshipped. This perhaps explains the view that “Dogs have masters, while cats have staff.”