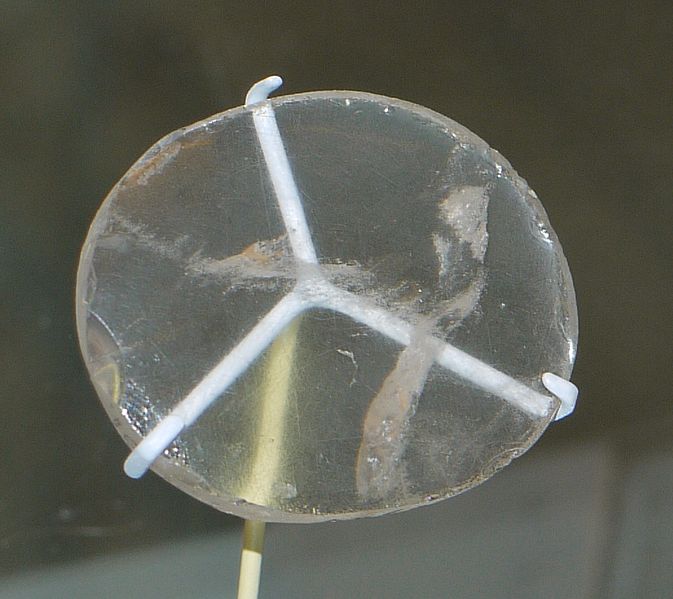

Figure 1 – Susse Frére camera in the collection of the Westlicht Photography Museum in Vienna, Austria. From the Wikipedia, image by Liudmila & Nelson and put into the public domain without restrictions.

Today I’d like to pick up on the story of the earliest cameras’s. The great french physicist François Arago revealed publicly the details of the daguerreotype process on August 19, 1839. Daguerre was a business man determined, much like technology entrepreneurs of today, to make a public success of his process. Two months earlier he had signed contracts with two manufacturers, Alphonse Giroux and Maison Susse Frères. Both of the manufacturers were granted exclusive rights to sell the modified camera obscura designed by Daguerre. Today only one Susse Frères daguerreotype camera, made in 1839, remains, or at least is known to remain, and is on display in the camera museum of the WestLicht auction house in Vienna, Austria. It is shown in Figure 1. The cameras made by the Alphonse Giroux et Compagnie, are almost identical.

The brass-mounted lens was produced by optician Charles Chevalier. It contains an 81 mm diameter meniscus achromatic doublet, (concave surface facing the front) and has a 382 mm focal length. In front of the lens is a fixed 27 mm diameter aperture and a manual picoting brass shutter. As a result the lens is approximately f/14.

The Giroux camera sold for 400 francs and the Susse Frères cameras for 350 francs. What does this translate to? There is a delightful link that describes the cost of things in Daumier’s time. It tells us that in 1838 the monthly salary of an unskilled laborer was 30 francs. Today we are told that is about $3,200. So we can estimate these early camera’s to have cost the equivalent of something on the order of $40,000!