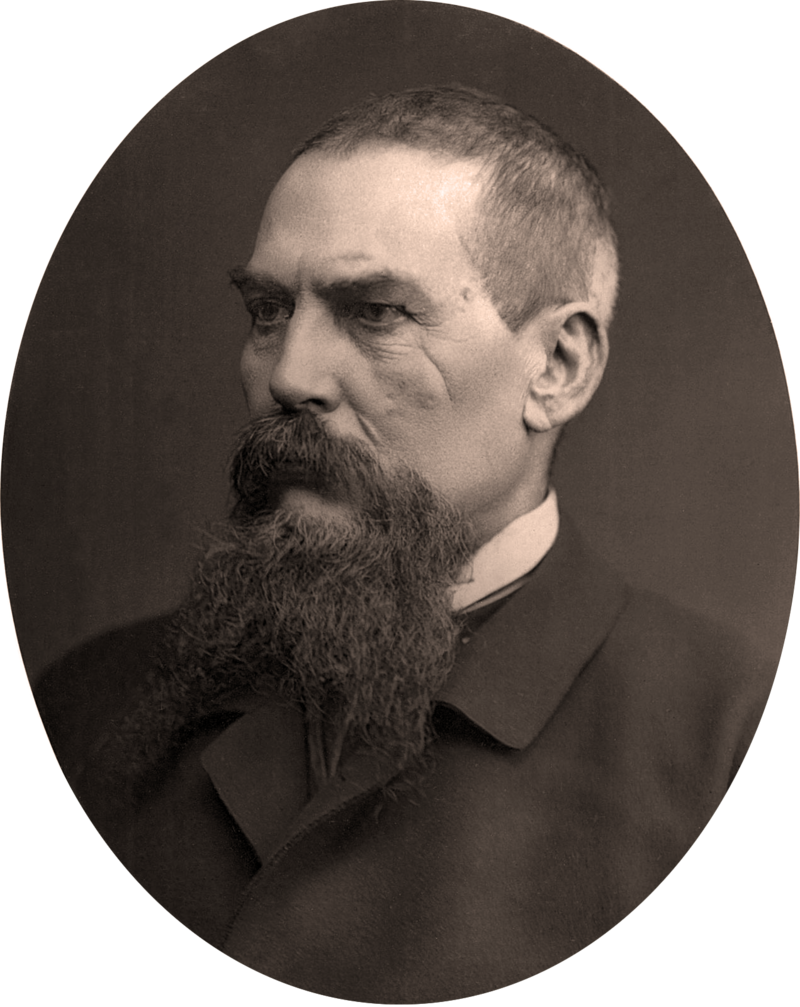

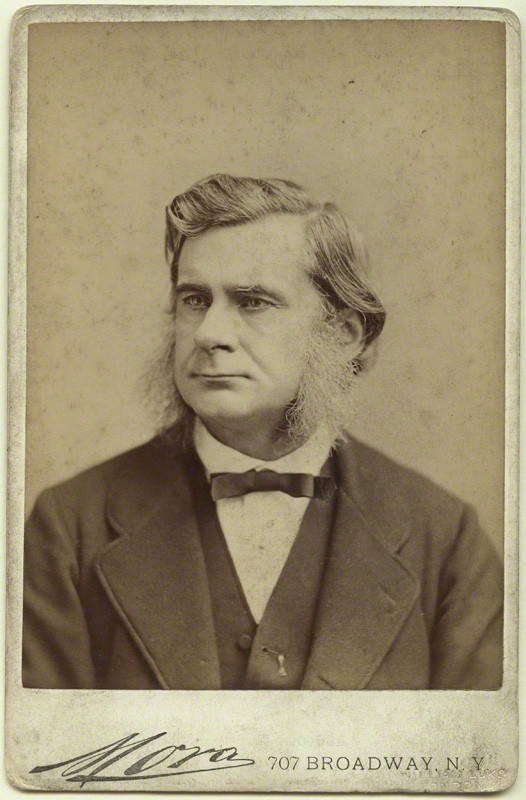

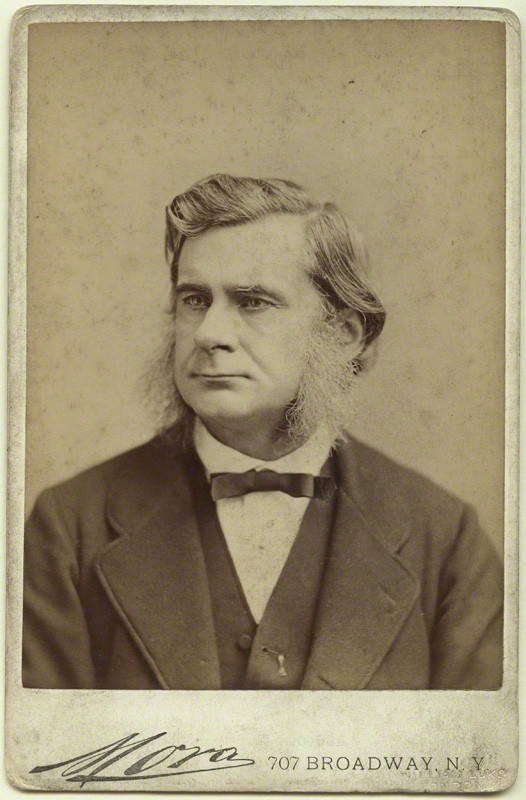

Figure 1 Thomas H. Huxley by Jose Maria Mora, albumen print, 1876 cabinet card, in the National Portrait Gallery London and in the public domain in the United States by virtue of its age.

Following in the footsteps of the great American portraitist, Napoleon Sarony was Jose Maria Mora (1846-1926). Mora was born to wealth and connection being a member of Cuba’s wealthiest plantation family. He studied painting in Paris. But the Cuban uprising of 1868 compelled him to return and join his exiled family in New York City, where he found employment with Napoleon Sarony and learned the photographic portrait trade. He was with Sarony for about two years, after which he set up his own studio at 707 Broadway, where he robustly competed with Sarony despite his mentor’s deep pockets and connections.

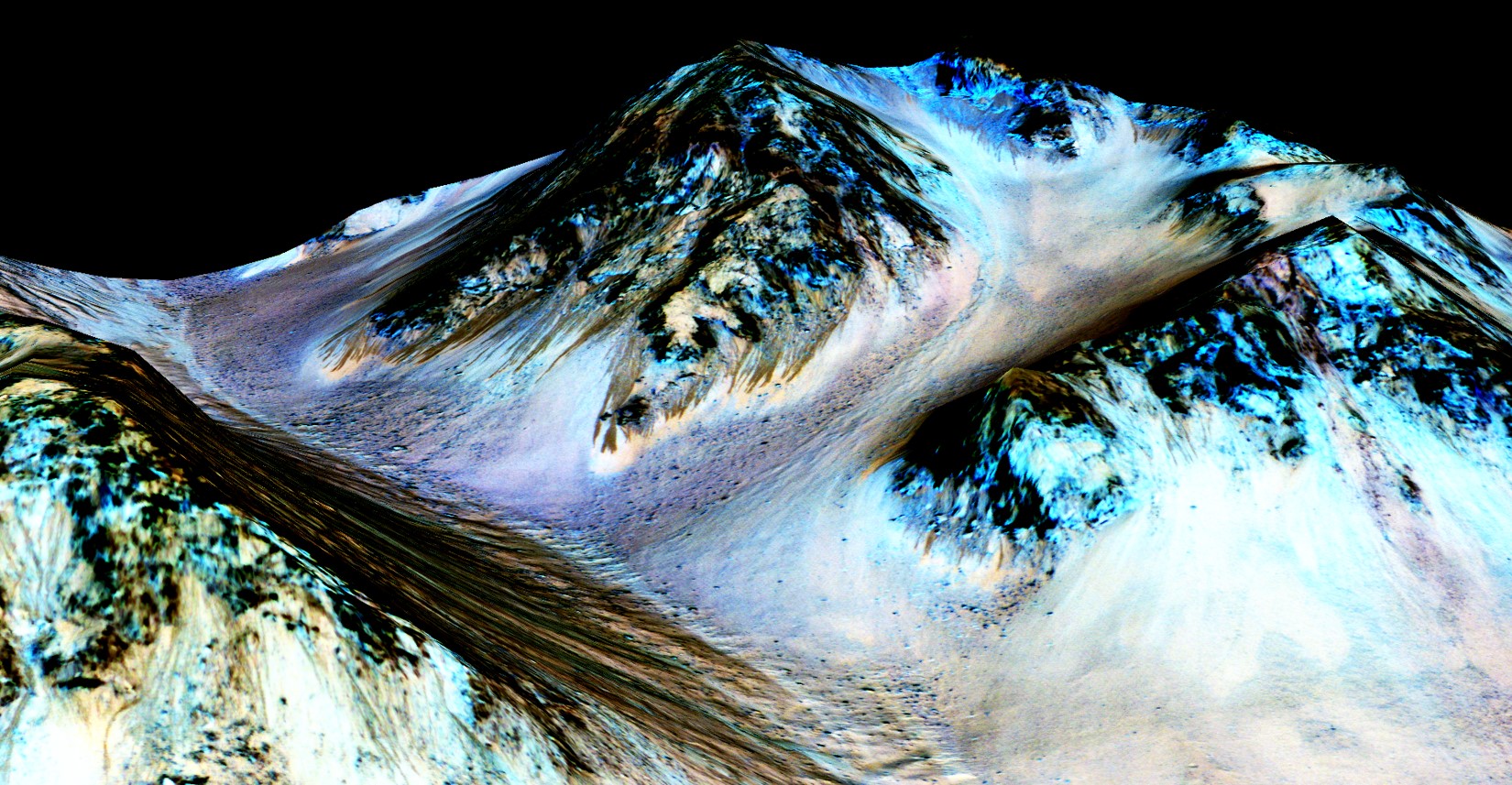

The “game” was celebrity photography, and the two studios competed vigorously for the exclusive right to photograph various visiting celebrities. Initially Mora competed by photographing the “second tier” actors and actresses of the day. Mora also had the largest variety of sets, or backdrops, of any photographer in the world supplied to him by the painter Lafayette Seavey. In the 1880s Mora became interested in photography as a medium for magazine publishing and formed arrangements with Harper’s, The Police Gazette, and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated, supplying images for engraving to support articles.

Unfortunately, it was around that point that Mora’s mental health began to deteriorate. He was embroiled in a family conflict with the Spanish government over the family’s holdings in Cuba. In 1895 he was awarded a sum of $200,000, a hefty amount in the day, but an amount that he found insulting. He deposited this money in a bank account and retreated to the Hotel Breslin, where he lived as a recluse until his death, subsisting on pies and cakes that were donated to him by other guests. When he died in 1926 the $200,000 remained intact and his hotel room was a relic gallery of theatrical artists of the 1890s.

To illustrate Jose Maria Mora’s work, I have chosen this portrait of the great British evolutionary biologist, “Darwin’s bulldog,” Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895). The National Gallery in London ascribes this portrait as having a date circa 1880. However, I believe that it can be more precisely dated as having been taken between August and September of 1876. During those dates Huxley was in the United States to speak at the dedication of the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore on September 12, 1876 and he traveled and lectured extensively along the east coast promoting Darwin’s theories. There is also a letter from Napoleon Sarony dated 16 September 1876 requesting that Huxley sit for him. Perhaps this was one battle that Mora won.

Regular readers know that I cannot let a great quote pass, and Thomas Huxley is a hero to scientists even today. As he entered New York Harbor Huxley was impressed by a nation whose skylines were defined by temples of learning rather than temples of worship. Huxley’s words at the Johns Hopkins still echo as a lesson today for those who confuse material success with true success:

“I cannot say that I am in the slightest degree impressed by your bigness, or your material resources, as such. Size is not grandeur, and territory does not make a nation. The great issue, about which hangs true sublimity, and the terror of overhanging fate, is what are you going to do with all these things?”