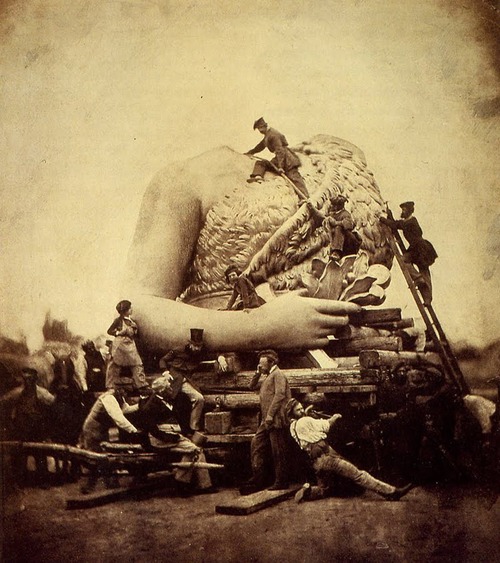

Figure 1 – John Robert Parson, Jane Burden Morris, c1865, posed by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. From the Wikipedia and in the public domain in the United States because of its age.

The last couple of days, when I was searching for exemplary albumen prints, I kept being drawn to a set of photographs like the one of Figure 1. It is a photograph of Jane Burden Morris (1839-1914), was taken in 1868 by John Robert Parsons (c. 1825–1909) and, interestingly, is often marked as posed by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882). The story itself is pretty straightforward. Rossetti commissioned Parsons to photograph Morris in poses of his choosing, presumably as photo-sketches upon which to base subsequent paintings. Indeed, I chose this particular example because it comes closest to a later colored chalk drawing of Jane Morris by Rossetti entitled “Reverie, 1868.” This is shown below as Figure 2. Beyond, that well: “It’s Complicated,” especially the love triangle between Rossetti, Jane Morris, and her husband William Morris (1834-1896), the founder of the English Arts and Crafts movement.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a founding member, along with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, of the secret (then) society known as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Indeed when they first exhibited these artists cryptically signed their work with the initials “P. R. B” after their names. The Brotherhood became a group of seven with the addition William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner. The goal of the group was to create a new movement in art, one defined by copying the extreme detail, intense colors, and complex compositions of nature. In particular they opposed what William Michael Rossetti called “sloshiness” (“anything lax or scamped in the process of painting”) that typified, in their minds, the work of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), who was a founder and first president of the Royal Academy of Arts. Most significantly, the group associated with and was championed by the great art critic John Ruskin, whom we have spoken about before.

Pre-Raphaelite painting often took on religious themes and the themes of English myths, Arthurian legend and the stories of Shakespeare. But they brought to these themes a new sense of human reality, which often seemed scandalous at the time. Clear examples of this are John Everett Millais’ 1850 painting “Christ in the House of his Parents,” where the holy family is reveal in a human not stylized fashion; and Rossetti’s 1850 painting “The Annunciation [of the Virgin] or Ecce Ancilla Domini,” where the surprised frightened somber expression on Mary’s face tells the whole story.

After 1856, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was responsible for the ‘medievalising strand’ of the movement, the turning of part of the movement towards medieval stories like Arthurian myth. Many of his paintings featured what we would today refer to as “femme fatales.” And the woman that he perceived as typifying pre-Raphaelite definition of beauty was Jane Morris. She was featured, in slightly awkward poses, in so many of his works, for instance as his Proserpine (1874).

Jane Morris was born in 1839, Jane Burden. Her father, Robert Burden, was a stableman and her mother Ann Maizey was a laundress. Thus she was that rarity in the England of her day, a woman who advanced in “class.” In 1857, Jane and her sister, Elizabeth, attended a performance of the Drury Lane Theatre Company in Oxford. Jane was noticed by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones who were then painting the Oxford Union murals, based on Arthurian tales. They were struck by her beauty and, they asked her to model for them. She was the model for Rossetti’s Guinevere and later for William Morris’ La Belle Iseult. Morris fell in love with Jane. Curiously by her own admission she was not in love with Morris.

Morris had Jane privately educated so that she would transform into a rich gentleman’s wife. She became proficient in French and Italian and was an accomplished pianist. If this story sounds familiar Jane it is because it was likely the real-life model for Vernon Lee‘s 1884 novel Miss Brown. This character in turn was the basis for Eliza Doolittle in Bernard Shaw’s play Pygmalion (1914) and the later film My Fair Lady.

Jane married William Morris in 1859. Now the plot thickened. In 1871 Morris and Rossetti took out a joint tenancy on Kelmscott Manor. Morris left on a trip to Iceland leaving Jane and Rossetti to spend the summer furnishing the house. It is believed that Jane and Rossetti’s intimate relationship began in 1865 and lasted until his death in 1882. It would be a disservice to this remarkable lady to confine her minibiography to her association with Rossetti and William Morris. She outlived both of these men. In 1884, Jane Morris met and became enamoured of the poet and political activist Wilfrid Scawen Blunt (1840-1922). Jane was also a dedicated proponent of Irish Home Rule. Jane Morris, was the muse and lover of two great artists of the 19th century and one poet. She was the real-life model and inspiration for Eliza Doolitle. And in her youth, she was the defining beauty of the pre-Raphaelite art movement

But what of John Roberts Parsons? There is remarkably little know about Parsons. Parsons grew up in the Irish County Cork and moved to London in 1840. From 1850 to about 1868, Parsons was a painter and exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts. Around 1860 he opend a photostudio in Portman Square. In the early 1870s Parsons partnered with Rossetti’s art dealer Charles Augustin Howell and in 1878 they set up an art studio on Wigmore street in London. He appears to have stopped photographing by 1878 . By 1888 he stopped exhibiting and died a decade later in seclusion. Mostly what we have of him are the remarkable portrait studies for Rossetti. We may at some level call him a mystery – though in all likelihood he was simply introverted and reclusive. There is a photograph of Parsons of unknown original and perhaps more significantly a photograph by him of William Morris in 1870.

Figure 1 – Dante Gabriel Rossetti, colored chalk drawing, “Reverie,1868.” in the public domain in the United States because of its age.

http://www.rossettiarchive.org/zoom/sa140eee.img.html