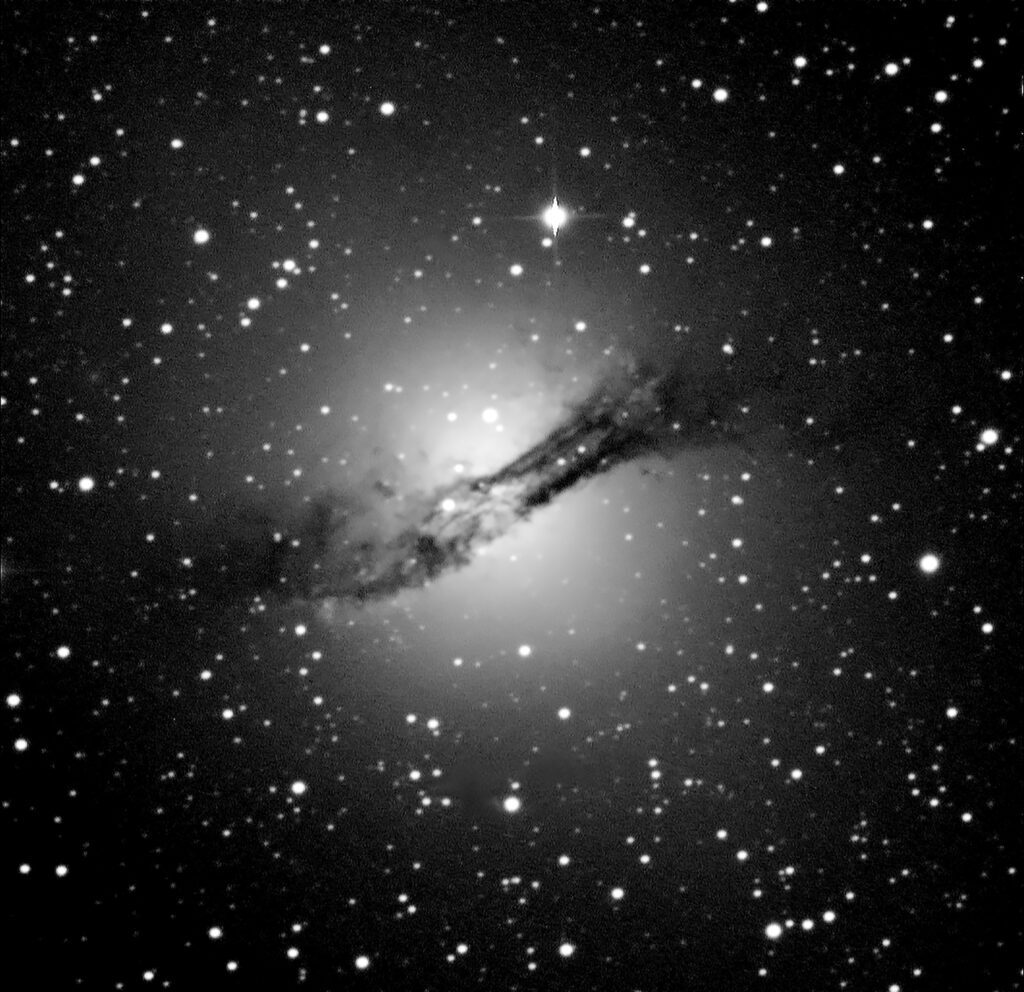

Figure 1 – NGC 7293 the Helix Nebula, SeeStar 30 min Image (c) DE Wolf 2024.

I wanted to talk a bit about relativity. You know what they say. “It’s all relative.” It has nothing to do with uncles, and cousins, and aunts. It has to do with the fundamental nature of the universe and the dominant force, when our perspective gets big, namely the force of gravity.

But let’s start with so-called reference frames, and this ultimately connects with Alice in the rabbit hole again – but I get ahead of myself. So let’s begin by imagining that its a sunny day in 1898 and you are sitting in London’s Piccadilly Station waiting for your train to depart the station. You are in the train, and it is motionless. As a Victorian you tend to be pretty confident in your assertions and beliefs. Suddenly you see and feel the station move backwards or perhaps better the train sitting next to yours, but then you realize that this is not the case. Actually, you are moving forward. Well that’s a relief. I mean how could that station be moving?

What is so disconcerting about the station moving? It is because we believe that stations are too massive to move. Hmm! Isn’t the station on the Earth rotating at about 1,670 km per hour? It’s time to grow up people and use the metric system! And isn’t the Earth revolving around the Sun at about 30 km per second? Yikes? And isn’t the Sun and Earth revolving around our Milky Way galaxy at about 200 km per second? Double yikes? And it goes on from there. The station and the Earth and the Sun are certainly moving and moving incredibly fast!

I will avoid mathematics here, but the thing is that to you, sitting in the train, from your perspective the station is moving. That is until you reject that conclusion on a faulty logic basis. From the perspective of someone on the train platform or on the neighboring train you and your train are moving. These perspectives are what are referred to as frames of reference.

Who is really moving? Which frame of reference is actually at rest? We don’t know. It’s all relative! I’d like to say that Einstein invented this concept. But he didn’t. It goes way back. Hence we have for instance Galilean (the Leaning Tower of Pisa guy) reference frames. We have a strong and prejudiced belief that there is an ultimate rest reference frame. There is not. It is all relative.

In Einstein’s view things do however get more interesting. Imagine that you see a little child in the front of the train and you throw a ball to him with a speed v. That’s how you see it at “rest” in your trains. What does a person at “rest” on the platform see? They see the ball move through space with the added speed of the train, call that V. So they see the ball moving at speed v+V. Pretty straight forward! That’s what’s referred to as a Galilean transformation. But the problem is that it was shown at the beginning of the twentieth century that the same is not true with light. If you shine a flashlight at the child it advances at the speed of light c. Same is true for what is measured by the person on the platform not V+c but just c. WTF?

This was Einstein’s great contribution and lies in the statement that it is all relative, that there is no preferred reference frame. If there is no preferred reference frame then the laws of physics must be the same in all reference frames. Suppose you have a laboratory and are at “rest” doing physical experiments. The laws of physics apply both in the laboratory and as seen by an observer, who thinks of himself at “rest” either walking past the laboratory or walking around it. Put that way the inviolability of the laws of physics is both intuitive and obvious.

But at the end of the nineteenth century the great achievement of physics was the unification of the theories of electricity and magnetism and optics. Those laws must be the same in all reference frames too. You might have on the train a small antenna with a current moving up and down. This generates an electromagnetic wave. And the velocity of that wave is the speed of light. But since no reference frame is preferred, there is no absolute rest reference frame, the wave as seen from the platform must have the same speed c. Wow! This as we shall see has enormous potential.

I hope that I have not given you a headache! And I think for our efforts we deserve a nice astrophotograph taken by yours truly on August 13, 2024 of the Helix Nebula NGC 7213 with my Seestar 50s. This image of a glorious planetary nebula is one of my best Seestar images and shows just what this little telescope is capable of. This last sentence is in honor of the cocky Victorians who believed that prepositions were not words to end sentences with. Such is not the case!