We’ve been having fun with our discussions of time travel. Or at least I have. 8<) I like the concept that a photograph fixes an instant in time and then that the observer can look at a set of photographs laid out on the table and flit between instances in a person’s life. The observer, at least, becomes Billy Pilgrim unstuck in time.

But then we explored the meaning of instantaneous in photography and recognized that there is an uncertainty of time and space coordinates associated with it. If you explore this further and go to the Oxford English Dictionary for a definition of the meaning of the word “instant,” what you find is two definitions for the noun: first a precise moment of time: come here this instant at that instant the sun came out; second very short space of time; a moment: for an instant the moon disappeared Photography achieves the second meaning. There is always a broadness to the moment.

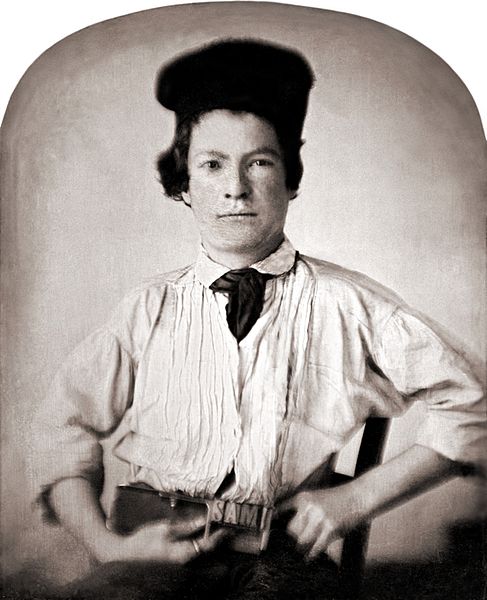

I wanted to share with you the little snapshot of Figure 1. It shows me at five years old with my grandparents: Mary and Louis Wolf. It’s not really all that clear, perhaps illustrating my points about fuzziness. I am pretty sure that it was taken with my first “Brownie” Kodak camera, which was actually the mocha color of chocolate milk and the lens was both simple and not very good. The pictures of my early youth were taken either with this camera or my father’s twin reflex Ciroflex. For birthday parties he would haul out this array of spotlights that literally blinded you – you say after images for hours.

One point that I want to make about this picture is that I am always dismayed by the fact that my parents and grandparents have no web presence. Arguably they should all be allowed to rest in peace. But we have come to associate web presence with significance. And, a fool trapped in the spirit of my own Zeitgeist, I cannot abide thinking of them as not having significance.

But there is a point or meaning to this little snap. I remember very vividly when we took it. We had been visiting my grandparents, probably on a Sunday. This was honestly a bit of a chore for a five year old. As a squirmy five year old I had to sit there rather bored as everyone spoke in a language that I didn’t understand. Still they were my grandparents and there is a special relationship between children and doting grandparents. It was time to leave and Mary and Louis had walked downstairs with us. Everyone was happy and we decided to arrange ourselves in this little pose to record the happiness and familiness. And that’s the very point. It was not a candid moment. It was a contrived arrangement of people, all with grins on their faces.

That is what portrait snapshots tend to be – contrived moments. I don’t mean this in a derogatory or sarcastic way. It is just that the subject conspires with the photographer to create an image of the subject in a way that the subject wishes to be seen. It is in that sense a contrivance.

The word “snapshot” always conjures up in my mind Joel Meyerowitz masterpiece, “An Afternoon at the Beach, 1983.” It seems to be a simple snapshot until you realize that the same set of people appear multiple times at multiple places in the picture. In a sense it is an exaggerated snapshot – that brings into ambiguity the concept of an instant in time. When we spoke about time travel, we spoke about the concept of parallel universes. Perhaps what Meyerowitz captures is the instantaneous convergence of a set of these parallel universes.