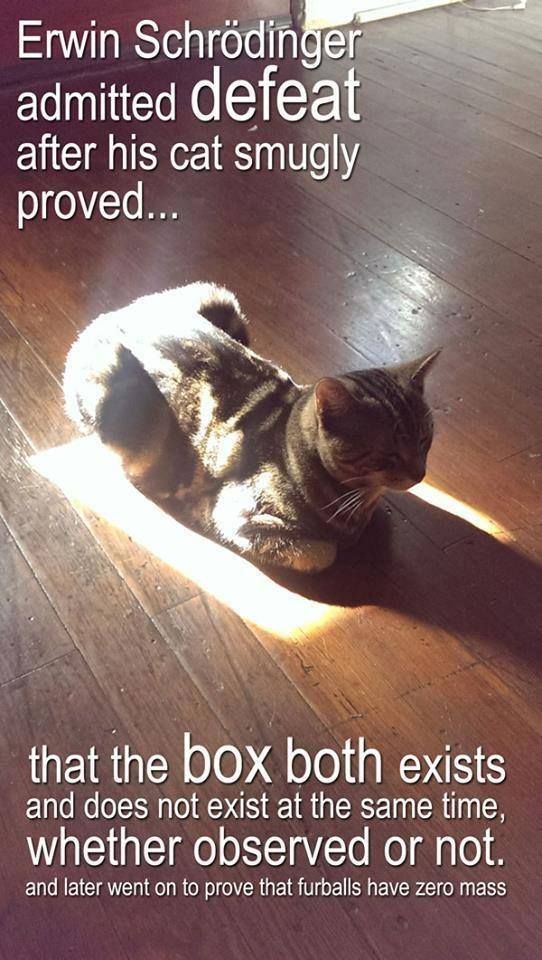

It is the last day of the year, which means that it is my last opportunity, at least for this annum, to do something that I have never done before on Hati and Skoll. That is to share something I’ve seen on social media. Several times this year I have seen or been sent the image of Figure 1. I do not know its origin. Erwin Schrodinger admitted defeat, when his cat smugly proved that the box both exists and does not exist at the same time…”

Obviously this is a jab at the whole Schrodinger cat in the box quantum entanglement thing. But it is so much more than a simple play on the meme of Schrodinger and his cat. As all lovers of things cat, physicists and otherwise, it is symbolic that ultimately the cat is master of his or her domain. And to the cat there is no ambiguity. The box is. The cat knows that it is, but asserts that if it is absolutely still and silent, you may not observe it. That is your problem, fur sure. Also Schrodinger’s assumption that there are two states of cat, alive and dead, ignores the fundamental quantum point that while dead is dead, the state of cat being alive is nine-fold degenerate. Also the transition of the cat between the dead state and one of the nine alive states requires the absorption or emission of a caton – not to be confused with a cation, which is something altogether different.

Now there is evidence that while Schrodinger lived in Oxford in the nineteen thirties that he owned a cat named Milton. This raises the question of why Schrodinger’s equation is based on the Hamiltonian rather than the Miltonian operator. In Hamiltonian mechanics two variables may be canonically conjugate in the Hamiltonian sense, while in Miltonian mechanics, they may be catatonically conjugate in the MIltonian sense. We may conclude, perhaps, that it should have been the Maltonian operator because, as pointed out by A. E Housman, “malt does more than Milton can to justify God’s ways to man.”

As natural as a cat sitting in the middle of a box-shaped sunbeam may be, it does point us to another principle of modern physics – the principle of relativity. Loosely the point is that if you do an experiment, say a chemical reaction, on a carousel, you will see the same results regardless if the observer is sitting on the carousel or on a park bench beside the carousel. “In physics, the principle of relativity is the requirement that the equations describing the laws of physics have the same form in all admissible frames of reference. For example, in the framework of special relativity the Maxwell equations have the same form in all inertial frames of reference“ – from the Wikipedia, if you prefer.

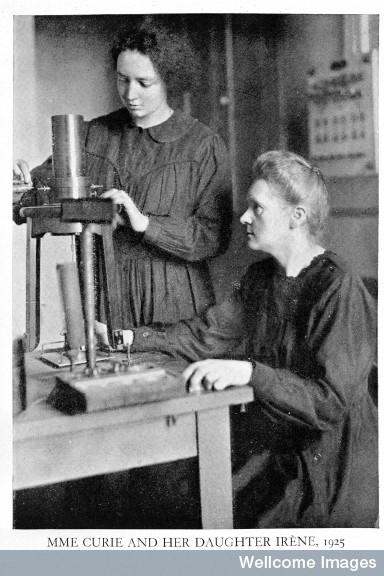

So from the cat’s frame of reference, you both exist and do not exist until you open the box and look in. Actually, truth be-knownst, the cat doesn’t really care if you exist until it is time to be fed. And finally, as shown in Figure 2, and as all cats know – the principle of relativity must be extended to take into account the fundamental feline recognition (for they are much wiser than thou or me) that the box is everywhere and in everything. Happy New Year, Everyone.