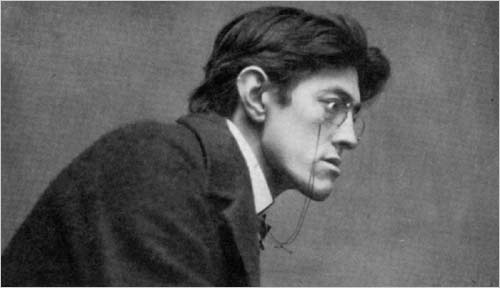

Figure 1 – Self Portrait of Zaida Ben-Yusuf 1901, from the Wikipedia and the US LOC, in the public domain.

The other morning when I was researching malapropisms for my post on “allegory bread,” I was taken aback to find a portrait of Miss Lydia Languish the protagonist of Sheridan’s play “The Rivals.” After all she is a fictional character. How could there be a photograph of her? Well, I suppose there are more bizarre things happening in “this best of all possible worlds.”

But as it turns out, and to set the balance of reality right, the photograph turned out to be a portrait of the end of century (19th – 20 th) actress Elsie Leslie in her role as Lydia Languish (1899) by“Zaida Ben-Yusuf (1869 – 1933). So we return to a favorite topic, namely 19th century portrait photographers and their salons. Ben-Yusuf was, indeed, one of the greats in this arena. You get the sense that New York City was crowded at the time with such studios. Ben-Yusuf’s studio was at 124 Fifth Avenue. She was noted for her artistic portraits of wealthy, fashionable, and famous Americans of the turn of the 19th–20th century. She was born in London to a German mother and an Algerian father. In 1901 the Ladies Home Journal featured her as one of “The Foremost Women Photographers in America.” Significantly in 1896, one of her studies was exhibited in London as part of an exhibition put on by The Linked Ring, the English counterpart to Steiglitz’s “Photo Secessionist” movement. She was a prolific writer and champion of photography as an art form.

For many years Miss Ben-Yusuf’s work and name had fallen into relative obscurity. However, in 2008, the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery mounted an exhibition dedicated to her work, and this has had the effect of re-establishing her as a key figure in the early development of fine art photography in America.

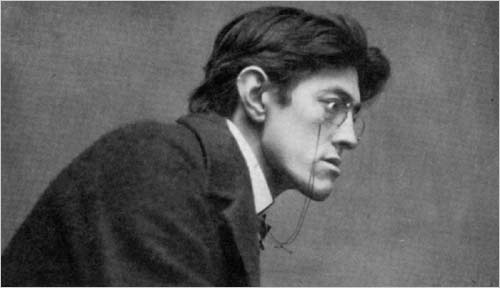

I wanted to feature here two of her Images. The first, Figure 1, is a self-portrait taken in 1901. It accompanied her article “The New Photography — What it has done and is doing for Modern Portraiture,” which was published in the “Metropolitan Magazine”, Vol. XIV, no. III (Sept, 1901), p. 391. The second image, Figure 2, is wonderful for its modernity and powerful pose is her 1899 portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann.

We find ourselves confronted again with nineteenth or early twentieth century visages and the complex set of emotions that they inspire. Have no delusions, it was a tough time to live, but in the United States at least, it was a time of great opportunity. This world of beautiful women clad in crinoline wearing pensive gazes like an army of Lydia Languishes is just exotic enough as to be appealing. Never mind that these are our grandparents and great grandparents. We want to believe that life was simpler then. It was not. The simplicity comes from the superior perch of hindsight. We know their stories. We know what is going to happen. For them a dangerous, life threatening infection was never far away. The great illusion here – the magic of photography – is that we almost feel that if we broke the silence, they could answer us.

Figure 1 – Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann by Zaida Ben-Yusuf, 1899. In the public domain in the United States because of its age.