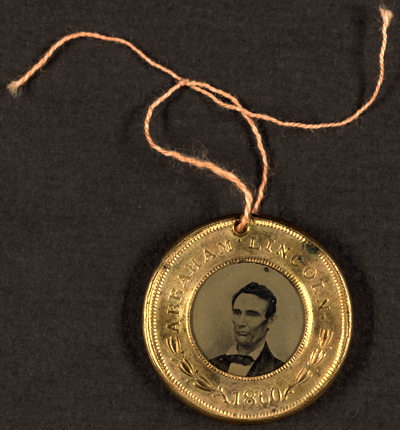

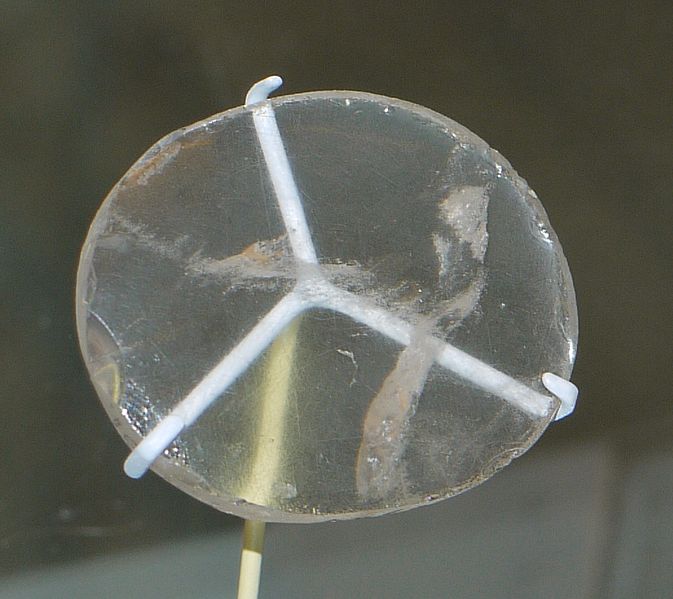

Figure 1 – Viking aspheric Visby Lens (11th to 12th century). From the Wikimedia Commons originally posted to Flickr.com, by Jonund and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license.

Yesterday, I discussed the mystery of Layard’s Nimrud Stone and sided with the British Museum’s view that it was a decorative object rather than either a magnifying glass or a burning stone. It should be noted that the view that it was possibly a functional lens was voiced by none other than the great Victorian physicist Sir David Brewster (1781-1868). Even if the British Museum is correct and the Nimrud stone never served as a functional lens, the question remains whether there were functional lenses in the ancient world or asked differently, when was the lens invented?

The answer is “absolutely,” as this quote from Aristophanes’ “The Clouds” proves.

STREPSIADES I have found a very clever way to annul that conviction; you will admit that much yourself.

SOCRATES What is it?

STREPSIADES Have you ever seen a beautiful, transparent stone at the druggists’,with which you may kindle fire?

SOCRATES You mean a crystal lens.

STREPSIADES That’s right. Well, now if I placed myself with this stone in the sun and a long way off from the clerk, while he was writing out the conviction, I could make all the wax, upon which the words were written, melt.

SOCRATES Well thought out, by the Graces!

Now “The Clouds” was first performed in 423 BCE; so the fifth century BCE, which is not really all that far from the Nimrud Stone wthat dates back to the seventh century BCE. And you can see by Aristophanes’ words that it is a pretty common place object in his day. Of course, you are skeptical of the name lens. Why call it a lens? The word lens comes from Lens culinaris the Latin name of the lentil, because a double-convex lens is lentil-shaped. The lentil plant also gives its name to a geometric figure. So Aristophanes is our earliest written record of lenses.

Some have argued that lenses were well-known to the ancient world.The writings of Pliny the Elder (23–79) show that burning-glasses were used by the Romans and also mentions how the emperor Nero (37-58) used a concave emerald as a corrective lens to help him watch gladiatorial games.

As we move into the eleventh and twelfth centuries ACE the use of lenses becomes well documented. Figure 1 is an example of a quartz lens excavated in the Viking harbor town of Fröjel, Gotland, Sweden 1999. These “Visby lenses” appear to have been produced turning on pole lathes. The lens of Figure 1 is encased in a beautiful silver mount, which may have been created later. These 11th to 12th century objects have imaging quality comparable to aspheric leneses produced in the 1950s.

Aspheric lenses are lenses that correct by shape for spherical aberration. That is a pretty sophisticated and some complicated mathematics is required to derive the required shape. But herein lies another marvelous paradox. The Viking craftsmen didn’t have knowledge of the mathematics needed, instead they worked by trial and error. Indeed, we may ask whether more than one craftsman actually possessed this knowledge. In any event it is a beautiful example of so-called “secret knowledge.” Perhaps most intriguing is the fact, a reverse on the paradox, that today when an optical engineer wants to design a complicated lens, (s)he uses Monte Carlo-based software. These programs are the modern day equivalent of trial and error.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.