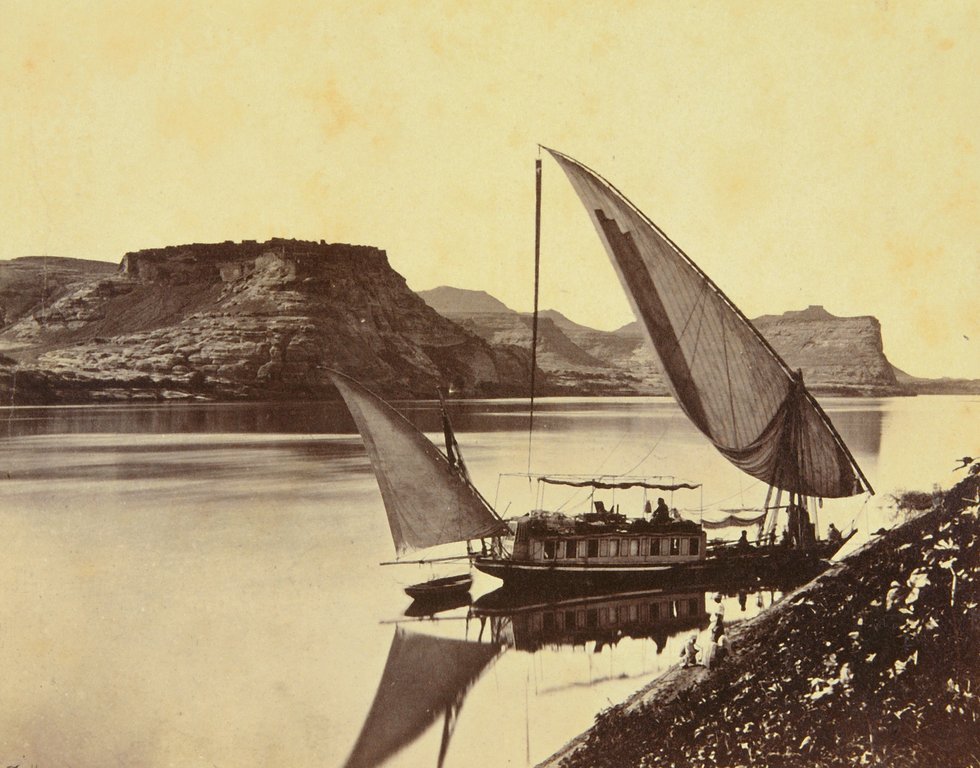

Figure 1 – The reception room at Sarony’s studio. c1870 and in the public domain by virtue of its age.

Last Sunday, I blogged about the great nineteenth century portraitist Napoleon Sarony. I have been doing more research on this colorful figure and I came across the fuzzy and pretty inferior image reproduced here as Figure 1, which shows the reception room of Sarony’s studio. At first, I thought that it was a mistake. The image appears to be that of a Wunderkammern, a cabinet of curiosities – or more literally a wonder room. The alligator hanging from the ceiling is oh so typical. Wunderkammern were the precursors of the modern museums. I have a friend, Keith Funston, who is an expert on Wunderkammern, and my first thought was that he would be interested in this photograph. As it turns out there is an extensive set of images of nineteenth century photographic studios on the Luminous Lint website.

I started looking for a sharper version of this photograph, and there the story got interesting because it took me to descriptions of what it was like to enter the world of Sarony’s studio, to step off of nineteenth century Broadway, NYC and have your portrait taken by the master. The moments of people’s lives that have been handed down to us come in two varieties: the “candid” or captured in their daily lives portraits and the formal studio portraits. In the case of the latter, this was, as Figure 1 attests, the taking was very different from what we experience today. It was truly a “gilded age” experience.

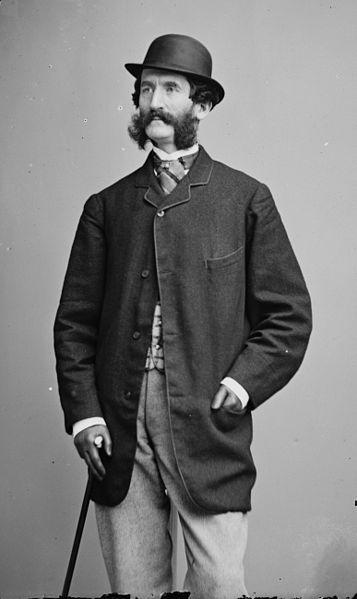

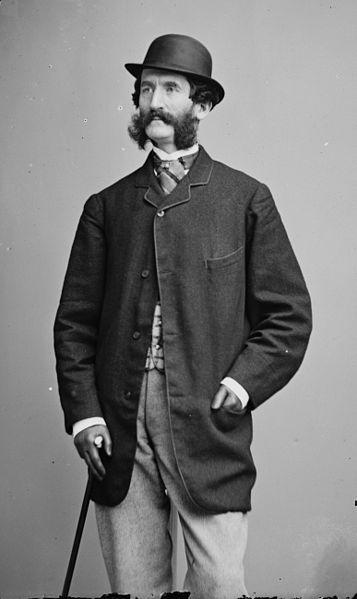

I was very struck by a description of a trip to Sarony’s studio written by Richard Grant White (1822-1885) in the March 1870 issue of the magazine, “The Galaxy.” We may reflect on this as we slowly watch the “magazine” as a media form shift from paper to electronic. There was a time when these were the most dominant form of information transfer. White was one of the leading music and literary critics of the day. Figure 2 is a portrait of White taken by another great nineteenth century photographic portraitist Mathew Brady (1822-1896). What struck my most vividly about the article was the quality of White’s writing. Now that is a largely lost art, but what we might expect from someone remembered today, albeit dimly, as a leading Shakespeare expert and English language defender.

I have decided, for those of you interested in reading it, (which I do recommend) to reproduce this article in its entirety here. It deals with photography as an art form and gets right to the pith, I think much better than Susan Sontag in her classic “On Photography.” There is, perhaps, a hint of sexism in his voice. I have avoided the use of the term misogynist. I do not think that these men hated women. It is perhaps to the contrary. But they did express the prejudices of the day and his description of an encounter with a coquette, so full of herself, is in a sense insightful. The man described was just a vain. To understand portraiture as an art is as much to comprehend the foibles of human vanity as it is to understand the technique.

You may recall, that I came to Napoleon Sarony from a portrait that he took of “The World’s First Supermodel, Evelyn Nesbit.” You may also recall that in “the crime of the century” Nesbit’s multi-millionaire husband, Harry Kendall Thaw, shot and murdered her lover, reknowned architect, Stanford White, on the rooftop theatre of Madison Square Garden on June 25, 1906. In a sense, we have come full circle. Richard Grant White was Stanford White’s father.

The vagaries of what and whom we remember is the irony of history. Richard Grant White, Harry Thaw, and Evelyn Nesbit are, perhaps, distant historical memories, footnotes as it were. Time has dealt with Stanford White differently. He is remembered for what he left behind – the buildings and monuments. It will soon be October, and I can tell you that in the crisp autumn air there will be no better place to wander with your camera than New York’s Washington Square Park. Look up. That wonderful arch, that is Stanford White.

Figure 2 – Richard Grant White by Mathew Brady, c 1860-1865 from the Wikipedia, original in the United States LOC Brady-Handy Collectyion, and in the public domain because of its age.

Richard Grant White, March 1870, “A Morning at Sarony’s”, from “The Galaxy, vol. 9, pp. 408-411.

A MORNING AT SARONY’S

“When Oliver Cromwell asked that his portrait should represent his face just as it was, wart and all, he not only showed a trait of his character and an habitual mood of his mind, but he took his stand on the side of a certain school of art, the realistic. When Queen Elizabeth insisted that hers should be painted without that ugly dark spot (the shadow) under the nose, she also not only displayed the personal vanity which was the swaying element of her nature, but she, too, threw the weight of her royal influence, though ignorantly, on the side of the other school of art, the idealistic. Cromwell wished to be painted as he was; Elizabeth as she seemed, or as she thought she seemed. It may by no means be safely assumed that Cromwell was absolutely right and Elizabeth absolutely wrong; for art should represent objects rather as they seem than as they are; if, indeed, representing them as they are does not show them as they seem. Of what value is a portrait, for example, which, although it represents exactly every line and tint of a face does not produce on the beholder the effect which the face itself produces? lt fails in attaining the highest and most essential point of faithfulness. Now there are such portraits—portraits correct in form and color, which are yet without individuality; a truthfulness which may appear in a sketch that is not Only unfinished but incomplete, a mere hint or memorandum for the painter.

Of such portraits photography produces hundreds of thousands yearly. When Daguerre discovered this method of using the chemical qualities of sunlight, it was supposed that one of the benefits to be conferred by it was perfect p0rtraiture of the human face and figure. And in truth it has made such portraiture attainable. But the experience of twenty-five years has proved that the attainment of such perfection is no mere result of delicate manipulation in applied chemistry. Photography, scouted at first by the painter—and with some reason—as a merely mechanical process, having only a certain utilitarian value, has been gradually rising until now it stands on the grade of a mixed art. lt is in a certain sense mechanical; the perfection of its results does in a measure depend upon the nicety of mechanical appliances and chemical manipulations; but to the attainment of its best effects in portraiture, and in even landscape, there goes something which is supplied by the sensitive organization and aesthetic culture of the operator. Otherwise, with good light and good chemical preparation, any person well taught and practised in the processes of photography could produce good portraits; and all persons so taught and practised would produce portraits equally correct and valuable. But the fact is, and it is now well known, that different operators produce different effects. Three photographers will produce three portraits of the same individual which are strikingly unlike, in spite of a certain likeness to their subject. And yet more, the same operator shall take three portraits of the same person within one quarter of an hour which shall be so unlike as hardly to be recognized as representations of the same individual. In a word, the photographer has become an artist. The eminent professors of the art have each his style, his individual manner, which is recognizable by an.acute and practised eye almost as easily as the manner of different painters. It is this style that gives their work its peculiar value and insures reputation, profit, success.

Do you suppose that mere chance, or command of resources, has enabled Brady to produce that superb array of the most distinguished men in the country? or that society decided blindly when Kurtz became the fashion ? or that Sarony’s reputation as the picturesque photographer is the consequence of his having happened to take good likenesses ofa few celebrated actors? Such things never merely happen; they are the results of natural gifts and hard study. Sarony’s portrait of Ristori as Marie Antoinette is a work of which Delaroche need not have been ashamed. True, it is the product of three factors. The skilful use of the chemical qualities of light, and the marvellous power of the actress herself in summoning into her face and attitude an expression of the emotions of the scene, are two; the third is the ability, the artistic ability, of the operator. He has succeeded in selecting, and then in fixing by a process almost instantaneous, the position and expression that will transmit Ristori’s grandest moment to posterity. The product is noble as a mere work of art. The portraiture aside, it is valuable for itself. There is mental anguish in every line of that face; there is tragedy in the very sweep of that drapery. Here is Bryant, most difficult of subjects, of whom the photographic and even the painted portraits are almost innumerable; but until these heads appeared nothing was quite satisfactory. This is the man: strong, simple, serene, benign, venerable. Here is not only the feature but the spirit. And in these portraits of Henry Ward Beecher, see the boldness, the subtlety, the flexibility, the intellectual and magnetic force, and also the humor, of the Plymouth Church ~preacher for the first time all embodied. A skilful artist with the pencil, Sarony has made the pictorial capacity of the camera a study. He can do with it almost anything within the range of the draughtsman‘s art—glorify or caricature at his will. Discarding those few formal poses so familiar and so oppressive in photographs, he is able to make true and characteristic portraits in positions so various and so free that they rival not only those of the portrait painters, but those in which figures are represented in genre or historical paintings. He is a master of light and shade, and produces heads which repeat the startling effects of Rembrandt’s etchings with a truthfulness to the facts of nature that Rembrandt in the attainment of his effect sometimes disregarded. See this head of a well-known and beautiful actress. The whole of the face is in shadow, except the high outlines of the features, and these are defined, not by shadows, but by brilliant lines of light. And there is a woman whom, having a beautiful profile and beautiful shoulders, Sarony boldly photographed with her back toward us, its fine undulations revealed in a broad mass of softened light, and her head turned so that we catch its finest outlines. Even if you have never seen the original, you covet this photograph as a fine picture.

These observations we make in the exhibition room, where Mr. Sarony’s business partner, Mr. Campbell, presides, as he does in every other part of the establishment except the operating room, where Sarony himself is absolute. For a great photographic establishment is a complicated affair, with many assistants mechanical and artistic, and must be directed with system and administrative ability. Mr. Sarony could not do so much work, or do it so well, were it not that he is relieved of this detail, and that another band runs the machine for which he supplies the steam. But Mr. Campbell intimates to a mild-eyed young lady that she can give us a pass to the operating room, and thus provided we ascend.

Glare, bareness, screens, iron instruments of torture, and a smell as of a drug and chemical warehouse on fire in the distance. A photographer’s operating room is always something between a barn, at green-room, and a laboratory. Here we find a few others like ourselves waiting their turns like the cripples at the pool of Bethesda. Sarony himself, no taller than his namesake Napoleon, and quite as peremptory, is listening to the complaints of a man who is dissatisfied with the proofs of his sitting. A hard-featured, money-making, Western pork-packer, who is fifty-five years old and looks every hour of it, in the hard lines of whose leathern face devotion to the one great object of life may be traced, it might naturally be supposed that he would be quite indifferent to the degree of youth and comeliness that appears in his portrait. Vain expectation! There are many astonishing revelations of human nature in the photographer’s rooms. Sarony and the sun have dealt kindly with this man, and have taken off at least five years from the record of time upon his face. But he is dissatisfied and ungrateful. He points out faults here and there, and Sarony with a crayon now softens an outline and now tempers an expression. But still the man, seeing himself as others see him, grumbles. At last the artist turns to him somewhat sharply, and yet with good nature, saying, “How young would you like to be made, sir? I could make you twenty-five, but my reputation could not bear that. Thirty-five is as low as 1 can go.” “Oh no,” is the reply, with a sudden manifestation of modesty, “make me look full forty-three,” drawing a fine line between forty and forty-five. “I’ll try to satisfy you, sir; ” and Adonis departs. How can he look himself in the face when he shaves those mahogany jaws tomorrow?

And now a lady steps forward for her sitting, an acquaintance with whom admits us with her behind the screen, but not quite to the artist’s satisfaction. For the photographer does not like to have the sitter’s attention diverted by even the consciousness of the presence of a third party. She begins to talk to him and he to watch her. He sees that she is pretty, but with that kind of prettiness which consists of expression, vivacity, and brightness of eye, more than regularity of feature. These are the most difficult faces to photograph satisfactorily to the friends of the sitter. He places her, makes her take two or three positions, tempers the shadows as many times by the adjustment of screens and curtains, and at last says suddenly, “There, so, if you please,” and sweeps his hand down the skirt and settles it with a look of satisfaction. The movement attracts her attention; and more concerned about her dress than herself, she turns her head quickly and gives her gown one of those pulls a little behind and below the waist that seem necessary to the perfect tranquillity of the female mind, and— an exclamation breaks from Mr. Sarony: “Ah, why could you not stand still as I placed you?” “But, my dress, sir!” “But me, madam!” with a tragicomic air, yet not without serious meaning. “Do I count for absolutely nothing in this matter?” Then turning to us: “it’s gone, hopelessly. One cannot do that twice immediately in succession.” The best is done that can be done, however, and the lady descends to give place to another.

The new-comer is a radiant beauty, who is accompanied by a gentleman whose admiration she accepts with the air of a queen receiving tribute. If she but knew how much more admirable a little graciousness would make her! He complains that of several photographers not one has done this lady justice, and exhibits half a dozen different cards. Mr. Sarony silently passes them to us, who boldly remain and assume the part of an assistant. The complaint is reasonable. Of all the portraits even the best degrades, vulgarizes, and grossens that lovely face, and two or three of them are so hideously unlike that they could not be recognized by either superficial or close examination. Strange, too; for the lady pr0ves to be a most docile sitter, and one of those who take position with grace and retain it with ease. Delighted with his subject, Sarony takes her in half a dozen different attitudes. She then asks to be allowed to make a slight change in her costume, and disappearing, returns in a few moments with her head-dress entirely changed, much simplified and diminished. Two more sittings in this state, and then the gentleman approaches her and asks a question. She plainly refuses a request. He evidently asks again, and she again says No. He presses his suit and becomes solicitous. Her cheek flushes, her docility vanishes, and the conversation becomes audible. “What! with no chignon at all, and my hair just dragged behind my ears! I never heard of such a thing; it’s perfectly preposterous.” “But you said you would; and that one will be worth all the rest.” “Well, I’m sure I’ve had two taken in braids, and nothing can be prettier than braids.” “Braids are very pretty, but there is one thing much prettier.” “What?” The question is asked not in words, but with a quick turn of the face and a look of inquiry. “Your head.” “Bother!” for she is beyond the mollifying effect of compliment. And, indeed, what woman is there who could be flattered into being photographed, or seen at a reception, without a head-dress or in a two-year-old bonnet, by being told that she would look as superb as Juno, as wise as Minerva, and as beautiful as Venus? So she says, “Bother! why do you want me to make a fright of myself?” His countenance falls, and she sees that he is sadly disappointed and even displeased. Her cheeks flush deeper, and her eyes glisten. “Well. if I must, I must ; ” and she begins to tear down her head-dress with reckless hands. “ You’re very unkind to make me do this just for your selfish pleasure ; ” and she bursts into tears of mingled grief and vexation; whereupon he evidently falls prostrate, and—as we can see by dumb show, for his voice is inaudible—entreats her not to do that to which she is so unwilling. But she has the bit between her teeth; and now she will do, despite his entreaties, what before she was so reluctant to do in compliance with them. Nothing so fell of purpose as a woman determined to be a martyr; and what martyrdom. what stake, what rack, what gibbet is equal to being pilloried without a fashionable head-dress that in five years will be ridiculous ! Disdaining the artifices of the toilet as unbecoming the solemnity of the occasion, with a turn of her hand she sweeps her hair behind her head and ascends the platform as if it were a scaffold. Her companion ventures to put out a finger to make some change in the position of the hair which is the cause of all this woe. Ignorant, presuming creature! She withers him with a glance, and draws herself away with a look that says, “Touch me not with unholy hands, for lam consecrated to sacrifice.” To Sarony, in his mingled office of high priest and executioner, she submits with a mien of offended dignity and edifying meekness. The portrait is taken; but what will come of that strange sitting probably only he and she, and her now utterly abject and humiliated companion, will ever know. G.”