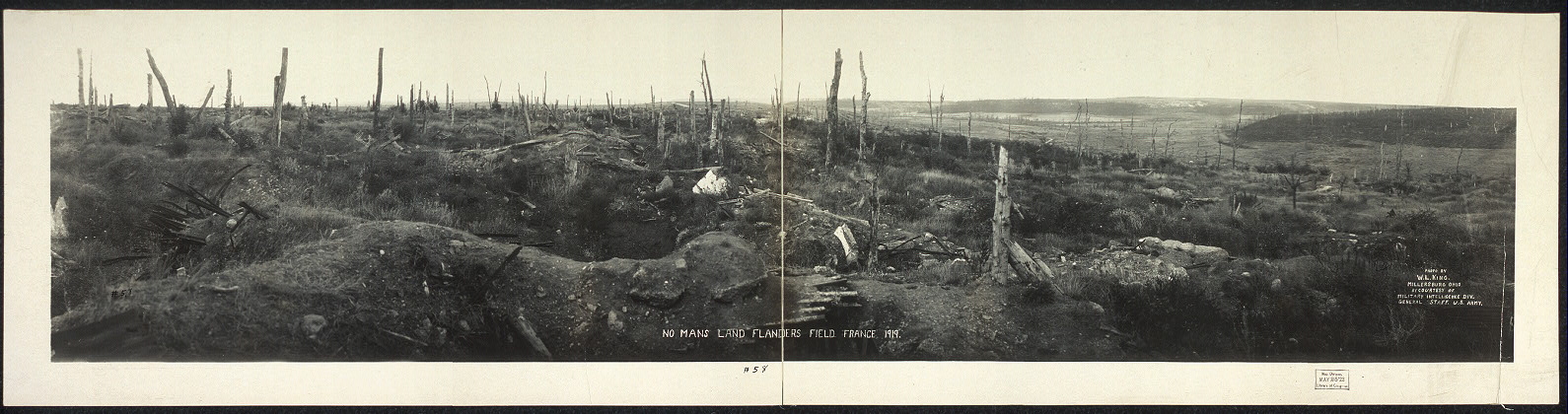

Figure 1 – “No man’s land in Flanders field, France, during World War I,” from the wikimediacommons, original in the US Library of Congress and in the public domain.

One hundred years ago today, July 28, 1914 Austro-Hungarian guns began firing in preparation for the invasion of Serbia. It was the ultimate folly, the opening shots of World War I or the “Great War,” and by the time it was over four and a half years later 10 million had died to be followed soon by 50 million succumbing to the Spanish Flu pandemic the the war’s end engendered. I say the ultimate folly, but watch the news tonight and wonder if we have learned anything.

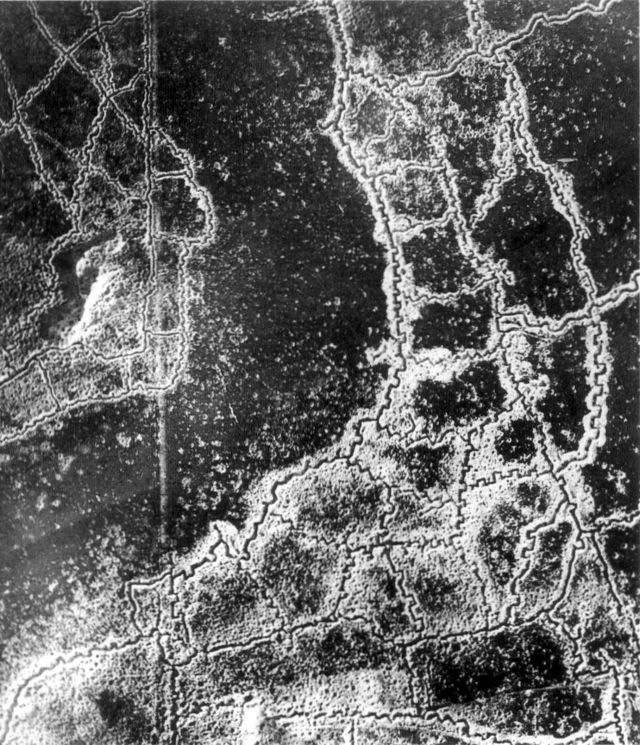

The First World War was well photographed. There are gruesome stills and even video footage of the misery and carnage. I thought that I would post a couple of images in tribute or remembrance. Figure 1 shows the “no man’s land” in Flanders, France a desolate, alien, and gruesome place. And Figure 2 is a different view of this nether world. It shows an aerial reconnaissance photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man’s land between Loos and Hulluch in Artois, France, taken at 7.15 pm, 22 July 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road or track.

“Zonder liefde, warme liefde

Sterft de zomer, de droeve zomer

En schuurt het zand over mijn land

Mijn platte land, mijn Vlaanderland.”+

+”Without love, warm love

The summer dies, the sad summer

And the sand scours my country

My flat country, my Flanders”

Jacques Brel, “Marieke”

Figure 2 – An aerial reconnaissance photograph of the opposing trenches and no-man’s land between Loos and Hulluch in Artois, France, taken at 7.15 pm, 22 July 1917. German trenches are at the right and bottom, British trenches are at the top left. The vertical line to the left of centre indicates the course of a pre-war road or track.

From the wikimediacommons, originally from the UK Imperial War Museums and in the public domain.