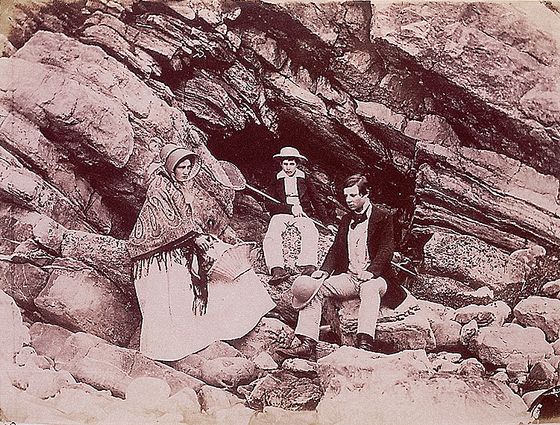

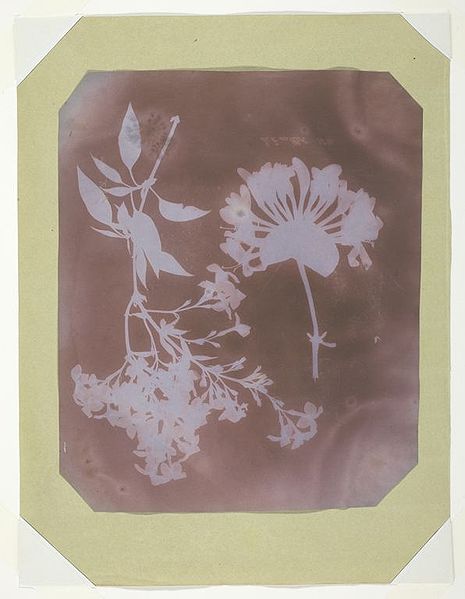

Figure 1 – Photogram by William Henry Fox Talbot of Two Plant Specimens, 1839

Photogenic drawing, stabilized (fixed) in ammonia or potassium bromide. Original source http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/artwork/38930 Edward E. Ayer Endowment in memory of Charles L. Hutchinson, 1972.325 From the Wikimedia Commons and in the public domain.

When you ponder the history of science or a technology, such as photography, it is very difficult, perhaps ultimately impossible, to be able to truly place yourself back and understand it as it was viewed at the time. Difficult or not, precious few ideas spring fully born like Athena from the head of Zeus, and we are invariably see the world through the filter of our own times.

To give an example from literature, Hamlet says: “The time is out of joint. O cursèd spite, that ever I was born to set it right!.” What ever does that mean? Indeed, in a sense with the evolution of language over the past centuries, Shakespearean English is perhaps 50% understood by modern speakers of the language. I mean really understood, because the plays address such human situations that we are truly compelled to understand. But to understand this comment by Hamlet, in fact much of Shakespeare, we must project ourselves back to an Elizabethan world view. They believed in a static, God created, unchanging world. Someone might disrupt the divine order with severe consequences. In this case it was Hamlet’s duty to undo this wrong and disruption of world order by his uncle. But, and here’s the catch twenty-two, in restructuring world order he would himself evoke change and could never be sure that his change wouldn’t be an equally wrong disruption. Pretty heavy stuff! Which is why Shakespeare has Henry V say: “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

Even in science this cross time understanding is strained. Scientist’s speak a language that is specific in an historical context. Very clearly scientists of today would have a hard, though probably not unbearable time, relating to the literature of a hundred years or more ago.

So back to photography, we can ask the question in what intellectual context did Daguerre and Fox Talbot evolve their discoveries. What was the language of chemistry and photophysics that they spoke?

A key predecessor of these two men was Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805). He lived so short a life and his discoveries lie almost forgotten. He has been credited with being the first person to conceive of writing with light on a surface. He knew how silver nitrate turned black, when exposed to light, and was the first to capture “negative images” by exposing them to sunlight. These were photograms, where an opaque object, such as a leaf, was placed upon the paper and it was then exposed to the sun which turned the unprotected regions black. Figure 1 shows a photogram created forty years later (1839) by Henry Fox Talbot.

The key problem that Wedgwood faced was that he could not figure out how to fix the image; so that it became permanent. He would take his pictures during the day and then show them to friends under candle light at night. This problem of fixation remained unsolved for almost the next forty years.

Thomas Wedgewood was also the first person (at least recorded person) to conceive of placing a photsensitive surface inside of a camera obscura and taking a true photograph. But his photosensitve surfaces were too slow. But there was the germ of an idea.

During a visit to the Pneumatic Clinic in Bristol for medical treatment, Wedgwood met and befriended Humphry Davy (1778–1829) then a young chemist. In the end it was Davy who published an account of Wedgwood’s work in London’s Journal of the Royal Institution (1802): “An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver. Invented by T. Wedgwood, Esq.”

Despite the fact that the Royal Institution was at that time somewhat obscure, this paper is believed to have play a seminal role in the subsequent invention of photography. As we have discussed often in this blog, silver nitrate chemistry has played a key and dominant role in film-based photography both monochrome and color. But time, science, and industry moves on, as does our understanding. Men such as Newton, Lavoisier, and Davy evolved (that is always the write word) away from alchemy and into a world where the fundamental mechanisms of these processes became understood. The electron was discovered. Electrochemistry became understood. Quantum mechanics and the photoelectric effect were discovered. All of this represented an ever changing level of understanding and, at each step in the road, a new nomenclature and way of describing.

An outcome of all of this evolution in human understanding is that sold state detector arrays were developed and these have changed photography forever. They have come to supersede silver nitrate-based photography, in the form of modern digital photography. And, of course, the question always remains: “What is next?”

* For those who prefer the printed word there is an excellent description of Thomas Wedgwood’s life and contributions to photography in Roger Watson’s and Helen Rappaport’s new book “Capturing the Light.”

![Figure 1 - Postcard produced: [ca. 1905] Summary: Translated caption reads: "French Congo. Passage of Mr. Administrator E. In the foreground, two leaders sitting in reclining chairs, in the background, village people and cabins. Congo Français. Photograph by J. Audema. General. In the public domain in the United States because of age.](http://www.hatiandskoll.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/800px-French_Colonial_administrator_Congo_1905.jpg)