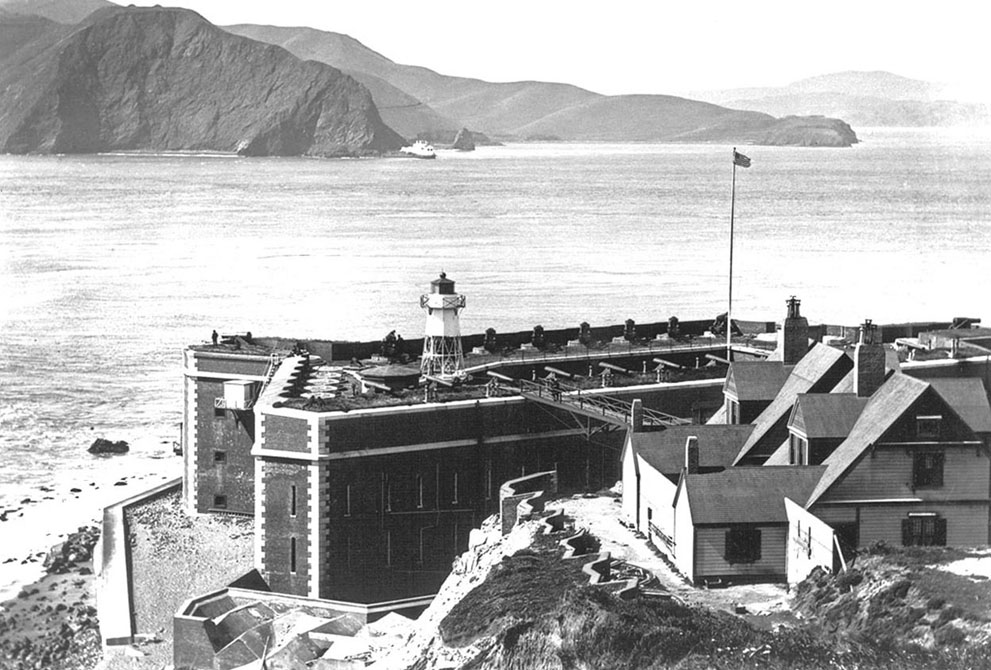

Figure 1 – a badly deteriorated piece of nitrocellulose photographic film, from the Library and Archives Canada / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada via the Wikipedia and in the public domain.

So, as promised, what about this nitrocellulose? We really need to project ourselves back to the late nineteenth century and imagine that we want to create a light weight portable film that doesn’t require loading a single glass plate at a time. Our goal, really George Eastman’s goal, was to create a flexible roll film. Nobody wanted to carry glass plates around. So you need a tough, clear,sheet material, and its being the late nineteenth century there aren’t too many choices.

The story really begins in 1832 with Henri Braconnot, who used nitric acid combined with starch or wood fibers to produce a lightweight combustible explosive material to which he gave the name xyloïdine. 1832?, you exclaim, that’s just before photography was invented. Then in 1838 Théophile-Jules Pelouze treated paper and cardboard in a similar manner to create nitramidine. Both of these were pretty unstable and not practical explosives. In 1846 Christian Friedrich Schönbein, finally found a practical solution. He mixed nitric acid with cotton, dried the material, and then there was a flash. Oh did I mention that he dried it on the oven door? I am reminded of a childhood limerick:

“Johny was a chemist.

A chemist he is no more.

For what he thought was H20 was H2SO4.

And it rained little Johny for a week!”

Schönbein and several other chemists worked on controlling the process, which eventually led to the creation of a material called “gun cotton.” Gun cotton was a usable explosive and was employed for all the good and bad uses you can imagine.

It was subsequently discovered that a suitable “plastic” (meaning flexible) sheet of Nitrocellulose could be made using camphor as a plasticizer. Starting in 1889, Eastman Kodak, starting in August 1889 used as the first flexible film base.It was used until 1933 for X-ray films and for motion picture film until 1951.

Though driven by the technical requirements of a clear and flexible film base, using a material also used for magicians’ flash paper and explosives, was not ideal – especially when used in conjunction with very bright and very hot movie projectors. Even worse, nitrocellulose, once burning, produces its own oxygen and as a result will continue to burn even when fully submerged in water. Projection rooms had to be lined with asbestos, and it was illegal to transport nitrocellulose movie films on the London underground.

Needless-to-say there were multiple fires caused by nitrocellulose movie film. In 1926 a cinema fire at Dromcolliher in County Limerick claimed the lives of forty-eight people. Sixty-nine children where killed in a theatre in Paisley, Scotland in 1929.

And then you have the coup de grace. The intrinsic instability of nitrocellulose, the very thing that makes it useful as an explosive, makes it a disaster from an archival point of view. It deteriorates very badly (see Figure 1). As a result old films, indeed the very films that represent the incunabula of cinema, are decaying. They are dangerous to store, dangerous to work with, and crumbling to explosive nothingness!