The twentieth century had its fair share of visionary and great men and women – people who pushed the out envelope. July 20, 1969, forty-four years ago yesterday, Neil Armstrong takes his first step on the moon.

Category Archives: History of Photography

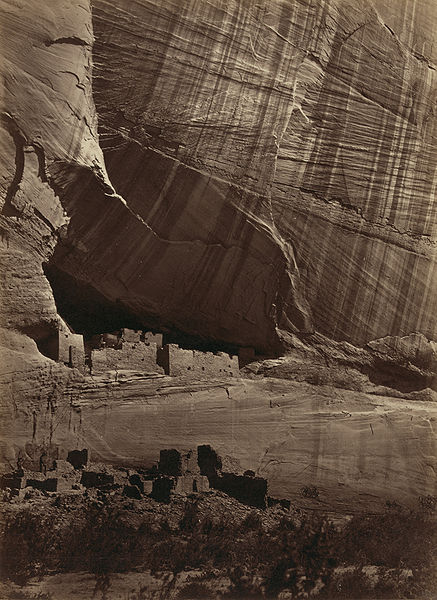

Timothy H. O’Sullivan

Figure 1 – Timothy H. O’Sullivan, Anasazi Ruins, 1873, from the Wikimedia Commons and the LOC in the public domain.

During the past week, I have spoken of nineteenth century American photographer Timothy O’Sullivan (1840-1882) twice, first in the context of his most famous and iconic images of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and second yesterday regarding his flashlamp images of Nevada miners.

O’Sullivan came to America from Ireland in 1842, While still in his teens, he worked for Mathew Brady. In 1861 at the outbreak of the American Civil War, O’Sullivan was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the Union Army. He appears to have principally been a surveyor for the army and he took photographs on the side.

In 1862 O’Sullivan was discharged from the army and was again employed by Brady, this time to follow the campaign of Maj. Gen. John Pope in Northern Virginia. He subsequently left Brady going to work for Alexander Gardner. This lead to publication of forty-four of his photographs in “Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War,” including his most famous photograph of dead soldiers at Gettysburg. After Gettysburg, O’Sullivan documented Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Petersburg and also photographed Robert E. Lee’s surrender at the Appomattox Court House in April 1865.

After the war and from 1867 to 1869, he was official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King. We have already discussed his flashlamp images documenting miner on the Constock Lode in Virginia City, Nevada. The goal of this work was to attract settlers to the American West and what O’Sullivan did was to document the rugged and beautiful American west. The term “geophotography” has been used to describe this genre of photography.

I have heard it criticized as being of a purely documentary nature. I believe this to be very far from the truth. These photographs bear both technical and artistic proficiency. They also speak to the wonder of human eyes when first confronted by awe inspiring nature. Significantly, O’Sullivan was also the first to document and record ancient American ruins, revealing that the white eyes of the nineteenth century were not really the first to occupy these spaces. That was an important lesson, one that ultimately defines America.

In 1870 O’Sullivan joined a survey team in Panama to explore the possibility of cutting a canal across the isthmus. Then from 1871 to 1874 he joined joined George M. Wheeler’s survey west of the 100th meridian west. O’Sullivan spent his final years in Washington, DC where he was the official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department. He died very prematurely of tuberculosis in 1882 at the age of forty-two. We can, however, say that his legacy lives on in the work of generations of American photographers, like Ansel Adams, who followed in his footsteps and photographed the natural beauty of the American West. This work still spell binds us and defines the American psyche.

Magnesium powder flash lamp photography

Figure 1 – Miner working inside the Comstock Mine, Virginia City, Nev. Taken by O’Sullivan using the glare of burning magnesium for a flash of light, 1867–68, form the Wikimedia Common and the US National Archives, in the public domain.

In a recent post, I discussed George Shiras III and his night time photography of wild animals. The lamps that Shiras used are also the ones that Jacob Riis took into the dark alleyways of the New York slums to record images for ground breaking social commentary “How the Other Half Lives.” There is an excellent website by Ivan Tolmachev that gives “A Brief History of Photographic Flash.” See also “Flash Photography.” and the photomemorabilia site.

To begin with, there was the sun. However, photographers desired to take their cameras indoors to film that part of life, and emulsions were very slow. Early film speed were roughly equivalent to an ISO of 4. The first reliable source of indoor lighting was limelight produced by heating a ball of calcium carbonate in an oxygen flame until it became incandescent. This process was also used to illuminate theaters, hence the phrase: “under the limelight.” Limelight was invented by Goldsworthy Gurney and used by L. Ibbetson as a source for photomictrography.

Limelight had its problems, not the least of which was the ghostlike flesh tones it produced. The French photographer Nadar, whom we have previously discussed in the context of early aerial photography, photographed the sewers in Paris, using battery-operated lighting. Arc-lamps were introduced to aid photographers, and in 1877 the first studio using electric light was opened. This Regent Street studio of Van der Weyde was powered by a gas-driven dynamo and enabled exposures of 2 to 3 seconds.

Edward Sonstadt commercialized the use of magnesium wire as a light source beginning in 1864 when it was demonstrated to produce a photograph in a darkened room with a 50 second exposure. Anyone who has burned magnesium ribbon in a chemistry lab, doused it in water, and watched it continue to burn will recognize that this was terrifying stuff.

An alternative was magnesium powder. In 1865 Charles Piazzi Smyth tried with poor success to photograph inside the pyramids at Giza, Egypt, with a mixture of magnesium and gunpowder. In the true tradition of the daguerreotypists, who worked with mercury and iodine vapors in very confined spaces, the lives, however short, of these photographers were filled with hazardous chemical explosions.

In 1887, Adolf Miethe and Johannes Gaedicke mixed fine magnesium powder with potassium chlorate to produce Blitzlicht. This was the first ever widely used flash powder. Typically these early flash powders were ignited with percussion caps. They were handheld and ignited with a pistol-like device. Then, in 1899 Joshua Cohen invented a lamp where the powder was ignited with a battery.

I think that there remained a terrifying aspect to these flash guns. There is highly demonstrative video showing one of these lamps in action. In the history of photography there were more than a few fatalities from these lamps.

English royal babies

Figure 1 – Calotype of Queen Victoria with the princess royal c1844-45. The earliest known photograph of Victoria. Image from the Wikimedia Commons from the Royal Archives UK and in the public domain.

At this point the world awaits the birth of Prince William and Princess Kate’s baby and heir heir to the British throne. The news coverage, or more accurately non-news coverage is endless. So I got to wondering whether there was a first photograph of Queen Victoria with with a baby Edward, Prince of Wales.

So far I have not been able to find one. But the story doesn’t end there. Queen Victoria’s first child Alice Maud Mary was born in 1843. The earliest known photograph, a calotype, of Queen Victoria was taken some time between 1844 and 1845. It is shown in Figure 1 and is, in fact, a joint portrait of the queen with the princess royal, who would at the time have been between one and two years old. The image is beautiful. It has that soft wistful quality that is typical of calotypes and is beautifully toned. While the custom of the day was to show rigid faces there remains something very endearing both about the queen gesture. the way her arm holds her daughter, and the little doll. The princess would certainly rather be playing!

Figure 2 – Photograph of the royal family on May 26, 1857 by Caldesi and Montecchi. From the Wikicommons and the Royal Archives UK, in the public domain.

There is also a wonderful image from May 26, 1857 by Caldesi and Montecchi, showing the Queen and Prince Albert with all of their nine children. This is shown in Figure 2. From left to right is: Alice, Arthur (later Duke of Connaught), The Prince Consort (Albert), The Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), Leopold (later Duke of Albany, in front of the Prince of Wales), Louise, Queen Victoria with Beatrice, Alfred (later Duke of Edinburgh), The Princess Royal (Victoria) and Helena. Again this appears to be a very gloom group. However, there are some very charming aspects to this photograph. The fact that everyone is not looking the camera, indeed Prince Albert is shown in profile, and the reflections in the window lend an informality, an almost candid quality, to the picture.

These images are further examples of the precious glimpses that we get of life in the nineteenth century during the first twenty years of photography. In some respects the sitters seem not quite sure how to deal with this new spontaneous medium. Many things, like photography, were evolving rapidly. Perhaps that is the most important lesson that we can learn from these pictures and think about when the new royal baby is born, indeed when any new baby comes into the world. There was a time when for Princess Alice in the first figure and for Princess Beatrice in the second that the world was new and the possibilities infinite.

Wildlife photography at night

A number of years ago I read an interesting little book by C. A. W. Guggisberg entitled “Early Wildlife Photographers.” one of the photographers that he discusses is George Shiras III(1859-1942), who was a US congressman from Pennsylvania, photographer, and wildlife enthusiast. Shiras won a Gold Medal at the 1900 Paris World Exhibition for what he referred to as his “Midnight Series.” In these images he was one of the first to experiment with flash light sources. He experimented with a lamp that could be held in one hand and fired like a pistol and also with trip wires that caused animals to photograph themselves.*

The perseverance required by nighttime wildlife photograph remains, despite all of the inventions that can claim to have made it “easier.” Over a century later we still marvel at such work. As a result, I was immediately drawn to a portfolio of nocturnal wildlife pictures called “Creatures of the Night.” I especially love the stroboscopic image of the northern flying squirrel, nut held tightly in mouth from Getty Images/Visuals Unlimited (Rocky would be proud); some very spookey camans by Frans Lanting of National Geographic and the bulldog bat also by Frans Lanting. OK, OK, I admit it, I love animal cute as much as anybody else. So be sure to check out the western tarsier clinging to a tree, again by Lanting.

This portfolio is one of those cases when we have to ask: what woud George Shiras say? He would have been in awe and amazed just like we are.

*A more detailed discussion of Shiras, images of him a work at night, and some of his early images can be seen at this site.

Images of the Battle of Gettysburg one hundred and fiftieth years later

Figure 1 – Iconic image of the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg taken by Timothy O’Sullivan the day after the battle July 4, 1863. From the LOC and in the public domain.

While we have discussed the importance of photographs of the American Civil War and the work of Timothy O’Sullivan for Mathew Brady, it remains significant that July 1 to 3, 2013 marked the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg. Many have viewed this battle as the “turning point” of the war as it marked the end of General Lee’s strategy to relieve pressure on Northern Virginia, the capital city of Richmond in particular, by invading the North and attacking the cities of Philadelphia and Baltimore apply a pincer grip on the Union capital of Washington, DC.

The losses at Gettysburg were staggering. The two armies suffered between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties over the three days of fighting. Figure 1 is the iconic image by Timothy O’Sullivan of the carnage and was taken the day after the battle. There has been a lot said about the brutality of the American Civil War. One theory has it that it was the first war fought with twentieth century weapons but eighteenth century tactics. Regardless I believe that it became too great a sacrifice merely for preservation of Union. The end of slavery became the goal of the war. And in a real sense the Civil War really was the second act of the American Revolution.

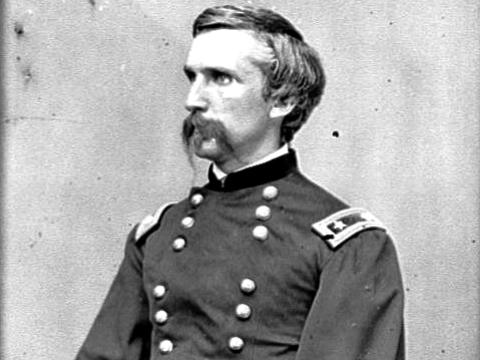

Figure 3 – Contemporary image of Joshua Chamberlain, who won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his defense of the Little Round Top, from the LOC and in the public domain.

The images of Gettysburg are iconic and legendary. Looking at the ones taken just after the battle enables us to transport ourselves back to that time and they enable us to attempt to understand. I don’t believe that true understanding is really possible but trying is a sacred duty.

Figure 2 is an image, possibly also by O’Sullivan, of the Little Round Top. Late on the afternoon of July 2, 1863, Union Colonel Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain led the 20th Maine Regiment in a desperate bayonet charge down the hill. Chamberlain is credited with saving Major General George Gordon Meade’s Army of the Potomac and ultimately of winning, winning the Battle of Gettysburg. Chamberlain won the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism on that day. A contemporary portrait is shown in Figure 3.

Finally there are two other images that may give us some sense of the meaning of Gettysburg – some further, at least, to help us ponder these events. The first, Figure 4, shows Lincoln at Gettysburg on the Day of his great address, November 19, 1863. And the second is of the last great Gettysburg reunion seventy-five years after the battle. 2500 blue and grey returned to that place one final time to remember. Figure 5 shows the blue and grey shaking hands across a stone wall.

The Vivian Maier Portfolios

Let me begin by saying that in my view the nineteen fifties were not the best of times for a first decade. But probably everyone feels that way about the awkwardness of childhood. Still I remember very itchy wool pants and a jar of hair lacquer named “Back to School” that remained in the family medicine cabinet far into the nineties – the thing was your hair could withstand a hurricane. I’m telling you this because I didn’t think that I could be made to be nostalgic about the fifties. But then yesterday a reader, Donna G., sent me this link, and I suddenly found myself amazingly transported!

The story is a peculiar one. Recently John Maloof found a treasure trove of negatives and prints in a auction. These pictures were taken over four decades from the fifties to the nineties, by a woman named Vivian Maier, who had worked as a nanny for several families, living mostly in New York City and Chicago. She led a secret life as a photographer, jealously guarding her secret, but at the same time amassing over 100,000 negatives and prints mostly taken with a twin lens reflex 2 1/4 ” x 2 1/4 ” camera.

The sensitivity of these sometime quirky images is marvelous. My father took pictures with such a camera and as a result, to me, they have a wonderful intimacy and take me back to a time when dirt was my friend and best friendships were born. I am so taken back that I am even wondering if the little blonde girl in one particular 1953 picture is my sister.

There are some truly wonderful portraits, many of children. One particularly striking 1956 image is of a beautiful young woman framed by a car window. This is a strange setting perhaps, although one she reverts to often, until you realize that it indeed is fitting and symbolic for the time of big cars. There are also some very clever self-portraits employing mirrors – distorted images in convex mirrors and infinities created by parallel mirrors. I am particularly fond of one obviously taken in a mirror store with fancy gilded baroque frames.

Maloof’s project to bring this fascinating woman and her work back to life is truly worthwhile, and it is quite an experience to step back in time and explore the website he has created. I think that for starters I have barely scratched the wonderful surface of Vivian Maier’s portfolios and am anxious to visit that world again. And, of course, I’m very grateful to Donna G. for introducing me to this fascinating body of work.

World’s first image of a hydrogen atom

From all of our discussions it should be clear by now what an incredibly visual species we are. It is in our genes. So it should be of no surprise that scientists are just as visual as everyone else. I used to think that biologists were pretty visual. If they couldn’t see, or at least picture something, they wouldn’t believe in it. I thought that physicists were , at least partially immune to all of this. You know, more abstract and mathematical in their thinking. But then I started to get excited the first time that I saw what are called nearfield images of single molecules of rows of benzene rings. And after that there was this wonderful electron microscope series of Uranium atoms dancing randomly in thermal motion.

But still, or so I thought, we were never going to see the structure of an individual atom. We were never going to see what are called the probability wave functions of say the hydrogen atom. In quantum mechanics objects like electrons and protons don’t occupy a single point in space rather where they are is a fuzzy area, and the mathematical formula that describes this area is called its probability wavefunction. This quantum mechanical phenomenon seemed safely sacred, something we had to calculate using Schrodinger’s equation (Yes, the guy with the cat) and then visualize in our minds eye.

Well, the thing is that physicists love a challenge and humans, especially scientists, take limits as challenges to our intellectual manhood. Still I was astonished today when I read that Aneta Stodolna of the FOM Institute for Atomic and Molecular Physics (AMOLF) in the Netherlands and her team have used a quantum or photoionization microscope to take the world’s first picture of the electron orbitals in the hydrogen atom.

This is really the stuff that “wows” are made of. It truly appeals to our need for confirmation of something abstract with our eyes. If we expand our definition of the camera, as I believe we must, to include other imaging devices and other regions of the spectrum, we are suddenly confronted by science at its best enabling us to see what was previously unseen. On an intellectual plane, I am reminded again of Tennyson’s Ulysses and the margins that forever fade against the unstoppable light of human endeavor. In physics this is something rare. So much of particle physics and astrophysics are not truly accessible visually. We are more often than not forced to take experimental results, put it in a mathematical context, and theorize. No one is ever going to see the Big Bang, for instance. Yet we can detect its remnants and see it with our mind’s eye.*

*HAMLET – “My father, methinks I see my father”

HORATIO – “Where, my lord?”

HAMLET – “In my minds eye, Horatio.”

Gruesome images from fifty years ago tomorrow

I guess that today’s blog falls into the baby boomers album of formative memories category again. Today’s images are so raw and intense however, that I am pretty sure that they will speak to everyone. Fifty years ago tomorrow, June 11, 1963, Malcolm Browne of the Associated Press covered a protest rally of Buddhist monks in Saigon protesting the oppressive actions of the South Vietnamese government against Buddhists. Suddenly Buddhist monk Thich Quang Duc sat down and his fellow monks doused him with five gallons of gasoline. Then Buddhist Thich Quang Duc lit a match.

It is as if the images are still burned into my retina and I still cringe reflexively when I see them. It was 1963 and it took fifteen hours for the shock wave to spread all around the globe. The event with pivotal in President Kennedy’s decision to escalate US involvement in the War in Vietnam. And as they say, the rest is history, very sad history.