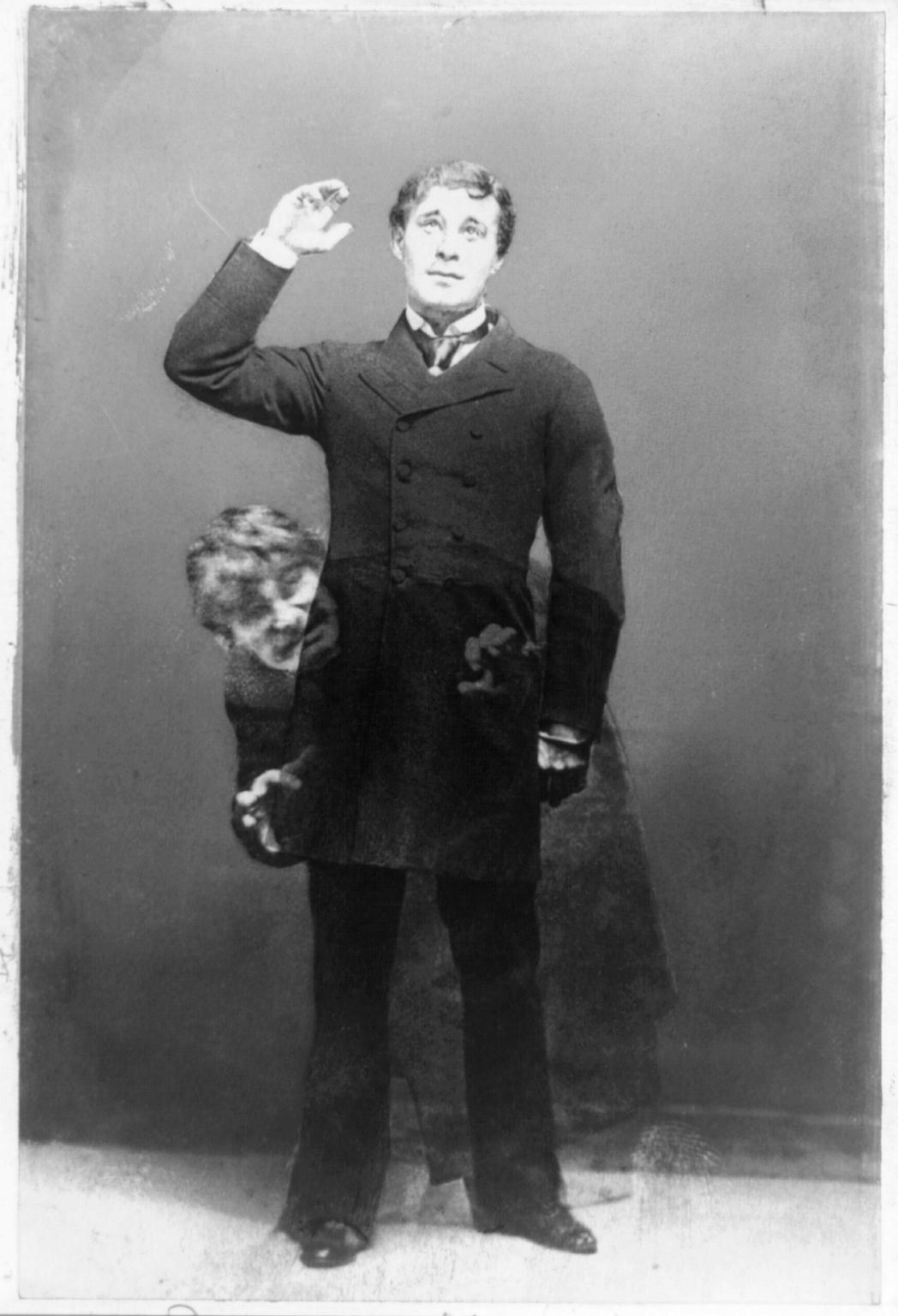

Figure 1 – Arnold Genthe (1869-1942)/LOC agc.7a15817. Miss Katharine Cornell with dog, 1917. From the USLOC, from the Wikipedia and in the public domain.

While researching yesterday’s blog, I started “reading up” on Katherine Cornell (1893-1974), who made Elizabeth in “The Barretts of Wimpole Street” her signature role. First of all, I have to say that my mother was a great fan of Katherine Cornell, who was widely acclaimed as the “First Lady of the Theater.” A striking beauty in her day, it is not surprising that she was photographed by some of the very greatest photographers of the first half of the twentieth century.

We can begin with Figure 1, a portrait by Arnold Genthe (1869-1942) take on December 31, 1917. It is so quintessentially Genthe. A soft focused figure appears as if out of the shadows in a chiaroscuro style. It was the height of photopictorialism, and the photograph speaks to classical roots in nineteenth century portraiture.When I first saw the image I assumed that she was holding Buzzer the Cat. But in fact, she is holding one of her spaniels. She was famous for her love of dogs. And, of course, Miss Barrett’s cocker spaniel, “Flush,” features prominently in “The Barretts of Wimpole Street.”

The second image is a portrait from 1924 by Edward Steichen (1879-1973). I am afraid that I am going to have to ask you to go to this link to see it. But it is worth the cyber-trip. There are many Steichen portraits of Cornell from this period and this one is such a masterpiece. You can see that it sold at auction at Christie’s for $87,762. It bears the same style as the Genthe portrait, only it puts Miss Cornell at the center, thus stabilizing the subject and the photograph. The subject has become statuesque, a dancer posing for the photographer. Cornell emerges now, no longer demur, but more vamp, that and her hat are typical of the feminine styles of the 1920’s.

Figure 2 – Carl van Vechten, Katherine Cornell, 1933, from the Wikipedia from the Van Vechten Collection at US Library of Congress and in the public domain.

Finally, we have Figure 2 a portrait of Cornell by portraitist and writer Carl van Vechten (1880-1964) from 1933. The lighting again is very similar, although the background is light, and the flowers are overwhelmingly translucent. Note how the flowers in the foreground brightly contrast and complement the dark wallpaper flowers in the background. They also preserve the “rule of thirds,” Still there is something disturbing here, a fear, and ingeniously the flowers accentuate the foreboding. Something is very, very wrong.

All three artists have chosen to portray Cornell in a similar light. It is the same persona dramatically transformed by the sixteen years that take us from Genthe to Steichen to van Vechten.

“I was nervous from the very beginning, and it got worse as the years went on. I was conscientious and wanted to do more, always, than I was able. I don’t think, when I was playing, that I was ever happy – beginning at 4 o’clock any afternoon.”

Katherine Cornell