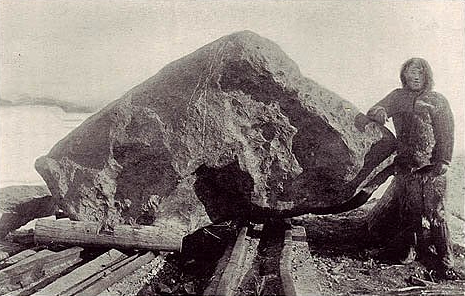

Figure 1 – Lon Chaney, Sr. from The Phantom of the Opera, 1925. Image from the Wikicommons and in the public domain.

Some time around 1925, my mother who was a young girl then, went with her friend Becky to the Loew’s Delancy in New York City to see Lon Chaney, Sr. (1883-1930), Mary Philbin (1902-1993), and Norman Kerry (1894-1956) in the silent film classic, “The Phantom of the Opera.” They screamed so loudly that they were almost thrown out of the theater. Watch the famous unmasking scene or even the entire movie and judge the terror for yourself. It is, of course, pretty thin by modern standards. Also take a look at Figure 1, a still shot from this movie, showing the horrific phantom. So the question I have to ask is this the movie that terrified my mother and her friend?

But first, let’s talk about the history of color in movies. In 2012 the National Media Museum in the UK announced an exciting discovery. The first color film was created by british inventor Edward Raymond Turner in 1902. Figure 2 is a still from the movie. This film was made with a special camera that took three successive black and white images through a red, green, and blue filters and then projected them back through the same filters. So fifty years after Maxwell’s tartan ribbon, we have the same technique applied to moving pictures. It is plain and simple pure additive color.

Figure 2 – A still from Edward R. Turner’s first color movie, 1902. From the British Media Museum and graciously in the public domain.

The first feature film taken and shown with an additive red green additive two color process called Kinemacolor was “A Visit to the Seaside,1908.” Of course, the use of just two colors was a bit limiting. In 1917 an additive technique that used four filters on a rotating filter wheel (red, yellow, green, and blue) was used to produce a film called “Our Navy.”

The dominant early color process was Technicolor. And it is with Technicolor that the subjects gets complicated and interesting. Technicolor came in three chronological stages.

Process 1 (1917) – the first Technicolor Process was additive and involved first taking the red an green images simultaneously onto sequential film frames using a beam splitter arrangement. The projector had two projection lenses. As anyone familiar with optics will recognize, this kind of projection will lead to a subtle parallax shift and the colors will not be in perfect registration. To overcome this, a wedgeprism was added to enable registration of the two color planes. There is an excellent photograph of one of these early Technicolor cameras and schematics of both the beam splitter camera system and the two lens projection system at the Wide Screen website. The first film produced by this process was “The Gulf Between, 1917.” Additive color was effective, but, as noted, required special cameras and projectors. The process also necessitated projection at double speed.

.

Figure 3 – A still from the masqued ball scene from the Technicolor Process 2 film, “The Phantom of the Opera, 1925.” From Wikicommons and in the public domain.

Process 2 (1922) – As a result, it soon became clear, necessity being the mother of invention, that subtractive color was the way to go. This led to adoption of the second Technicolor process. Again, as in Technicolor Process 1, images were taken red and green simultaneously on film. The red and green sets were then photographed onto two separate strips and dyed in the complementary color. They were then cemented together. The first film produced by this method was “The Toll of the Sea, 1922.” “Phantom of the Opera was made by the Technicolor Process 2 in 1925. Wait a minute! Phantom of the Opera was a color movie. Yes indeed it was. Only a small segment of this remains of the masqued ball scene (see Figure 3) . So why is it now only seen in black and white? We’ll get to that part of the story later.

Some of you are old enough to remember films melting from the heat of the projector, or even worse, for nitrocellulose based films, exploding or bursting into flames. Projector heat was a real problem for films produced by the Technicolor 2 process. They warped and buckled and the two layers would separate.

Process 3 (1928) – To overcome this heat problem the third Technicolor process was developed. Once again red and green planes were recorded simultaneously but sequentially on the film. However, in the developing laboratory the reds were copied to one strip of film and the greens to another, just like in the Technicolor 2. However, the film contained a special gelatin. The gelatin required exposure to UV light to copy the films. The UV hardened the emulsions. Unhardened emulsion, that is unexposed emulsion, was removed chemically. This is very reminiscent of Nicéphore Niépce’s (1765 – 1833) method of creating the world’s first photograph, which we have discussed previously. The emulsions were then dyed with complementary colors and chemically transferred to a “blank” strip of film. A so-called “mordant” was then applied to prevent further migration of the emulsion. The first film produced by the Technicolor 3 process was “The Viking, 1928” (video of the entire film).” This was also the first feature-length Technicolor film to also feature a soundtrack.

Wikipedia has a list of early color movies and the processes used to make them. The list covers the period from 1903 to 1935. Take a look at this list. It is astounding how many there were and how strong audience demand for the latest technology must have been. We have Autochromes and Three Color stills. We have brilliant and magnificent color movies by a variety of additive and subtractive processes, most dominantly Technicolor. These all are a tribute to the inventiveness and color of the age. I for one can never think of this period as being a black and white one.

OK. So why do most of these films now exist only in black and white? First, of all in the 1940’s the company Technicolor destroyed many film originals, when they were unclaimed by the studios during a space clearing act. Most of those that survived were made into black and white for television copies in the 1950’s and the colored masters were subsequently destroyed. So the real black and white era was not the 1900’s to 1920’s but the 1950’s to 1960’s – the era of black and white television.

For further reading on Technicolor see the Wikipedia and the Wide Screen website. Both of these were consulted extensive in researching this blog.