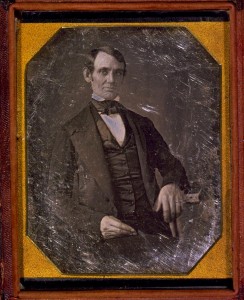

Julia Margaret Cameron Portrait of Sir John Herschel with Cap, 1867

I absolutely love the photographs of Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-1879). So this was a tough call for me. I kept going back and forth between this photograph and her “Annie, my first success, 1864.” But in the end, the physicist in me won out. Sir John Herschel ((1792-1871)) was a great British astronomer. Here he is depicted as an old man. He seems a wild man with his hair out of control beneath his cap. It is the expression in the eyes that makes the image. You know that those eyes have peered for many hours through telescopes discovering the wonders of the universe. The three quarter view is always an interesting one. Sir Herschel looks to the side, not at the photographer, as if abstracted, his mind on something else. Perhaps he ponders some problem in celestial mechanics. We will never know. I find it wonderful.

Cameron was one of the founders of photography. There is a excellent book entitled “The Golden Age of British Photography 1839 – 1900,” in which she is described as a “Christian Pictoralist.” This is very accurate, as illustrated both in her choice of subject matter: mother and child, little girls with pasted on angel wings, and posed allegory: and in the value she attached to her own works: “My mortal, yet divine! Art of photography.”

While many of these themes might not appeal to our twenty-first century sensibilities. They accurately depict the religiosity of the nineteenth. Julia Margaret Cameron was a photographic innovator, and the pensive, dreamy poses of her subjects still move us nearly a century and a half after she took them.