Let us take a break from technical issues today and recognize that photography is ultimately about art. The technical aspects are to be mastered like learning to paint. Technical proficiency is a necessary step towards achieving a subjective vision of what is in front of the camera.

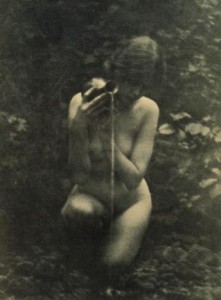

Figure 1 – Anne Brigman “The Source, 1909” From wikimedia.org

This is essentially the view of the photo-secessionist movement founded by Alfred Stieglitz and Holland Day in 1902. Stieglitz and Day’s photo-secessionist group mirrored a British coterie, “The Ring,” that had seceded from “The Royal Photographic Society.” This view that photography was about pictoralism, not so much about accurate depiction as about manipulation of the image by the photographer to achieve his/her artistic goals was, at the time, highly radical. And in that sense, it ushered in a new century in photography.

A quintessential member of this movement was California photographer Annie Brigman, who is famous for her nudes photographed in rustic settings, usually the Sierra Nevada. She heavily reworked her negatives to achieve classic mythic imagery that often paralleled significant paintings. I, personally, discovered Brigman at the RISD Museum “America In View” exhibit and, honestly, some of her works take my breath away. They appeal to a deeply engrained sense of the spiritual.

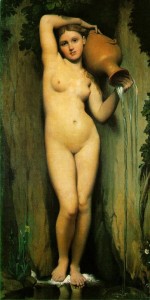

Figure 2 – Photograph of Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres’ “The Source, 1856” in the Musée d’Orsay. From wikimedia.org

Anne Wardrope Nott Brigman was born in Honolulu in 1869. In 1885 she moved to Los Gatos, CA. In 1894, she married sea captain Martin Brigman and accompanied him on several journeys to the South Seas. Around 1900, she settled in San Francisco and became active in the Bohemian community. Stieglitz listed her as an official member of the secessionist movement in 1902. Between 1903 and 1908 her photographs were featured in several issues of Stieglitz’s photo-secessionist journal “Camera Work.” Brigman became a significant figure and highly revered in the community of California artists and photographers. A major retrospective of her photographs and poetry, “Song of a Pagan,” was published in 1949 a year before her death.

Three of her works standout in my mind. These are: “The Source,” first published in Camera Work in 1909; “The Bubble,” also first published in Camera Work in 1909, and “Figure in Landscape, 1923.”

The source depicts a female nude pouring water on the ground from a clay urn. Needless-to-say this evokes the mythic sense of the mother goddess, sanctifying the Earth, and the source of a great and nourishing ancient river, such as the Nile. It is a classic image as evidenced by the similarly titled work by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres in the Musée d’Orsay.

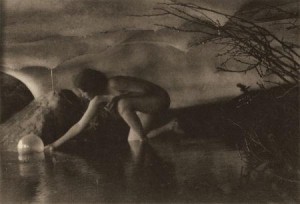

Figure 3 – Anne Brigman, “The Bubble, 1909,” from wikimedia.org

“The Bubble” is a fantastic image of a female nude, creating and launching a bubble on a mystic stream. The references to the mother goddess again seem clear and engrained. The bubble, which appears in several of Brigman’s works, evokes the ovum from which we are all born. The river is not only the birth canal but the river of life on which we must all journey.

“The Figure in Landscape” is something quite different. A female nude stands in the distance on a ledge above a lake. She looks away from us, perhaps about to take the risk and dive into the water. For me, this creates a sense of the possibilities of youth, heightened by the unspoiled purity of the American wilderness. I have read that Brigman typically photographed herself or the rugged and self-assured young women that had the strength to live and thrive in the Sierra Nevada. It is cliché now to say that the twentieth century was the American Century. But in a sense this lone figure, like the photo-secession itself, seems to open and define that century.