A reader(ABW) has asked me to comment on a recent posting on the PetaPixel website concerning the creation by photographer “Michael “Nick” Nichols”, under the auspices of the National Geographic Society, of a giant image of the second largest Sequoia in the Sequoia National Forest, “The President.”. I was all set to do so, when another reader (CJHinsch) responded so elegantly to my New Year’s Resolution post, expressing my desire to learn to photograph trees, and further pointed me to the work of James Balog. Mr. Hinsch really hits the nail on the head. The real issue is not the marvel of how this is done technically, but the marvel of the tree itself, and that’s a very personal thing. So more discussion on all of this needs to happen.

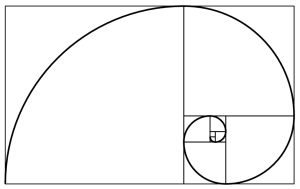

As far as the tree mosaics are concerned, the technical need for this type of image is the recognition of two points: First, if you try to photograph a tree from its base, or suspended in another tree, or even from the air you are going to wind up with a pretty distorted image or a very tiny one from far away. Second, that’s not how the eye works. We see the tree in its entirety, then focus in on a few leaves, see them in fine detail, perhaps even notice a caterpillar. Finally, we focus back and in our minds eye imagine that we have seen the whole tree at the caterpillar level of detail. So if your desire is to reproduce the human experience “tree” in it’s full scale entirety, this is what you need to do.

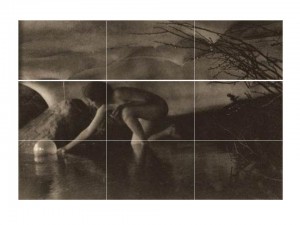

Recognize that trees are not the only subjects that call out for this type of treatment. This happens whenever we are confronted by a subject that is physically larger than our lens can handle, unless, of course, we step way way back and lose all detail. It should also be said removal of distortion is not always the artistic intent. In the case of the tree images the goal is presenting a sharp and highly resolved undistorted image. But there are other cases, making a 360 degree image of a landscape, where the distortion is intentional as a means of adding drama. Moving frame by frame perpendicular to an image removes distortion. Rotating around the axis of your tripod actually introduces a so called “spherical distortion.”

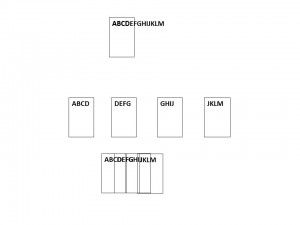

Doing a mosaic is conceptually pretty straight forward and is illustrated in Figure 1. Imagine that I want to photograph something that is way too large to fit in my field of view, here the letters ABCDEFGHIJKLM. In fact, my camera can only photograph five letters at a time. What I do is take four overlapping images. Then I reconstruct them by overlapping the images.

Doing a mosaic is conceptually pretty straight forward and is illustrated in Figure 1. Imagine that I want to photograph something that is way too large to fit in my field of view, here the letters ABCDEFGHIJKLM. In fact, my camera can only photograph five letters at a time. What I do is take four overlapping images. Then I reconstruct them by overlapping the images.

Now in the age of digital photography, this is an automated process. Your Iphone or IPad will do it for you (have apps.) as will Photoshop. When photography was a purely analog, this was a laborious and painstaking process. But could be very effectively done, as witnessed by Ansel Adams’ giant landscapes for the Wells Fargo Bank. It still is pretty laborious as the Sequoia project illustrates. The desire is to keep things perfectly flat so as to minimize distortion and the need for corrected algorithms. In the case of the tree image the camera is moved up down and sidewards snapping multiple images on a hoist and framework. The advantages of creating an image this way is that it is flat and undistorted and it has a much higher level of detail than could be accomplished with a single image. In fact the major limitation in practice tends to be how big and at what resolution can you print.

That’s it technically, but like I said there’s a whole lot more to consider from a aesthetic and emotional viewpoint.